- OT

- CPD and education

- Visual impairment, employment and empowerment

- Visual impairment, employment and empowerment

Visual impairment, employment and empowerment

This CET article describes the impact of visual impairment in the workplace and the role that practitioners can play in helping these patients

Introduction

In the year 2010, just over 600 people of working age were newly registered for severe sight impairment (SSI) or sight impairment (SI) in Scotland.1 For many years, the leading cause of SSI in working age adults was diabetic retinopathy (DRP)/maculopathy, but this has now become the second leading cause of blindness after inherited retinal disease in England and Wales according to data from 2010.2 However, the Royal National Institute for Blind People (RNIB) states that DRP/maculopathy remains the leading cause of ‘avoidable sight loss’ among the working age population in the UK.3

Sight loss has an immediate impact on employment. In 2015, around one in four registered (SI or SSI) people in the working age population were in paid employment, compared to around three in four in the general population.4 SI and SSI people of working age are significantly more likely to receive housing and council tax benefit,5 and twice as likely to be living in a household with an income of less than £300 a week.

Why are visually impaired people under-represented in the workplace? It has been reported that 27% of non-working registered people left their last job due to the onset of sight loss or deterioration of sight. However, more people would stay in employment with the right support.6 Receiving specialist vision rehabilitation support improves confidence and independence and aids in the acquisition of new skills.7

In this article, different scenarios will be discussed to illustrate how visual impairment can affect employment and what positive steps can be made to support people of working age.

Case one: diabetic eye disease

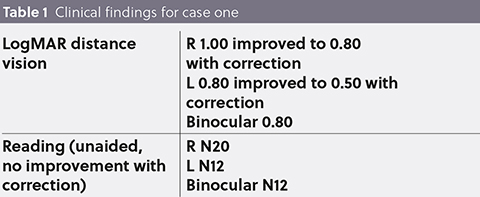

This first case demonstrates the effect of sudden visual loss in adults of working age, in this scenario due to diabetic eye disease. Table 1 summarises the clinical details.

A sudden drop in vision could mean that the day-to-day work duties either have to be adapted or changed and in some cases a patient may not be able to continue in the role that they are employed for. Sudden involuntary unemployment can lead to depression, anxiety,8 and fear,9 and this is exactly what this patient is experiencing.

In this case, the patient works freelance, which means that there is a sudden loss of income for him. The low vision practitioner needs to be equipped to deal with both the emotional stress and employment issues.

Although some practical support can be offered in terms of optical aids, there is a much wider issue here that demands input from many different agencies. Some of the issues will be discussed here.

In this scenario, driving a car is an essential part of the job and also the ability to see small details close-up. As both of these skills are now compromised, the patient has decided to take unpaid leave. As many people in the UK have limited financial reserves,10 this scenario can lead to significant distress. With money running out at the end of the month, this patient is worried about not being able to pay his rent.

What financial support is available? How can this patient be supported in the workplace?

Distance vision and driving

This patient is undergoing intravitreal treatment for maculopathy. Once the condition has settled, refraction will need to be repeated in order to establish if driving can be resumed. In the meantime, the patient is advised not to drive as his vision is unstable and below driving standards.

Near vision

In the workplace, this patient felt that the use of magnifiers was unacceptable for various reasons. In the author’s experience, patients often cite that they do not want to be perceived as someone with a visual impairment. Unfortunately, the stigma associated with the use of low vision aids still exists and a better understanding of visual impairment within general society and the workplace may reduce this stigma.11

It was decided to focus on prescribing magnifiers for the home situation during this visit and perhaps consider adaptations in the workplace at a later date.

A dome magnifier provides enough magnification for fluent reading tasks, allowing an acuity reserve of 2:1.12 For reading labels and instructions with small print and poor contrast, an illuminated hand magnifier, for example, of around 3.5x magnification is a good option. For patients with access to a smartphone, assistive technology can be explored. Simple advice can be given during the consultation. For further support the practitioner can refer to local technology sessions for the visually impaired.

Work

The Equality Act 2010 protects employees with a disability,13 and it is helpful to be familiar with referral pathways to provide the right employment support. In this case, a same-day referral was made, and options were discussed to support this patient in the workplace. It is worth referring to the nearest eye clinic liaison officer (ECLO) as they often offer same-day assessment and advice. In this case, the ECLO arranged a benefits check (for long-term financial support) and tactile stickers to highlight dials and switches.

Diabetes control

Good glycaemic control is important to prevent further visual loss. It is, therefore, important to address this issue and make sure that the patient is able to manage their medication. For instance, audio or large display glucose meters can be obtained.

This case scenario demonstrates that positive changes can be made to support a patient with their employment and finances. However, it is unrealistic to expect changes to be made overnight and, therefore, some time is needed to set realistic goals and expectations. One also needs to consider the emotional impact and offer low vision aids at a time when the patient is ready to accept interventions of this type.

Case two: cerebral palsy

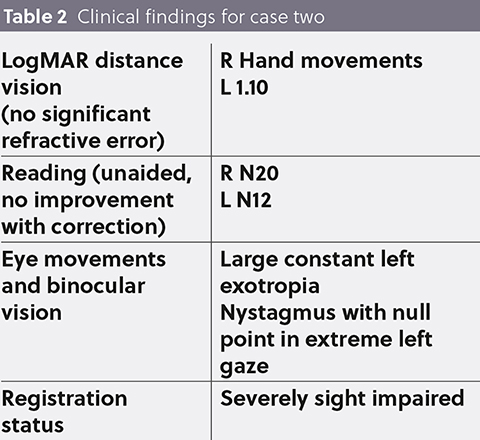

This second scenario is an example of a patient who has had to cope with ups and downs in employment and has made some positive changes to improve his work situation. A man of working age presents to the hospital eye service (HES) with a history of cerebral palsy (CP) with left hemiplegia. Table 2 shows the relevant clinical findings of this visit.

He had been in a job where he felt unwelcome with his disability for many years, despite actually being able to do the job, using a telescopic aid. Reports of this type where individuals have unsatisfactory work experiences can lead to them eventually giving up.14 Although the Equality Act 2010 sets out to protect people with SI or SSI in the workplace, the reality is that some people can find it difficult to function in employment. The unemployment rate in young people with CP and average intelligence, is higher than in the general population, while 28% of people with CP in employment have experienced situational or health barriers.15 Despite these barriers, the patient in this case decided to get further education with a view to achieving more satisfying job prospects. Since taking this proactive approach, for the past few years he has been working in a new environment where he is valued and appreciated.

He has been using a 4x spectacle-mounted left monocular telescope for many years and he finds this extremely useful. It has the right amount of magnification for what he needs to see, and it has a flexible working distance without the need to hold a magnifier, which is ideal with his hemiplegia. Adaptation to a distance telescope is enhanced when the user understands the benefits and restrictions of the device, as seen in this case.16 Although this patient had tried various other low vision aids over the years, the telescopic aid remained the best option. A new telescopic aid was fitted for the right eye using a focusable Keplerian system mounted into a system frame offering magnification of 4.2x and 5x at distance and near, respectively (see Figure 1).

This case shows that a patient with CP, who had negative experiences in employment, could overcome these barriers due to his own perseverance and initiative, combined with the right support. For some patients, more support is needed and referral to other agencies, such as the RNIB or Access to Work services may be required. They can offer support in the current workplace or explore different career pathways, education and training.

Case three: macular disease

This scenario is an example of a working-age patient who has adapted to deterioration of vision over many years. The patient initially had visual impairment in one eye, which was soon followed by vision loss in the other eye; this caused problems in her work situation as she needed to see very small details, including written manuscripts. However, she didn’t identify herself as being visually impaired. Denial is a common initial reaction to visual impairment17 and, throughout this stage, patients tend to resist the use of magnifiers. The way the diagnosis is communicated can affect how the patient will react,18 so it is important to take time to explain the condition and answer any questions the patient may have. A positive initial consultation tends to lead to better acceptance and a good rapport, which is essential for optimal management of these patients. In this case, a simple pair of high-add spectacles was sufficient to compensate for the patient’s reduced acuity. However, as her vision deteriorated over time, a different solution was needed. At this stage, the patient was in a transition from considering herself as being sighted to identifying as visually impaired; this is the point at which patients typically start to accept the need for compensation strategies and interventions such as magnifiers.19 They start to recognise that assistive devices and adaptive lifestyle changes promote independence and competence as well as safety. The patient was now ready to request an assessment from Access to Work in order to make some changes in the workplace, such as better lighting and extra time to complete tasks. She was issued with an electronic pocket magnifier to enable her to see manuscripts. For certain tasks, the use of magnifiers and telescopic aids worked very well. When her vision deteriorated further, higher magnification aids and a CCTV were issued to enable her to continue to work. She also started to use voice recognition and audio technology in her workplace. When it was no longer possible to deal with written manuscripts, she was moved to a different role where she could function better with her visual impairment. In order for her to get to the workplace, she was referred to the RNIB for mobility training and technology sessions to familiarise herself with navigation apps.

As can be seen in this case, deteriorating sight constantly changes the needs of the patient and new adaptations and devices need to be considered at each step. A good relationship and continuity of care is essential to meet the evolving needs of patients with deteriorating vision.

Figure 1

Conclusion

These cases have shown that the low vision practitioner can play an important role to support visually impaired patients in the workplace. However, more can be done with better support from the government to reduce the stigma attached to sight loss as well as provision of specialist education and resources to support patients in the workplace. Jamie Hepburn (MSP for Business, Fair Work and Skills) has announced ‘A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People: Employment Action Plan,’ in which he commits to achieve the ambition to at least halve the disability employment gap over the next 20 years. The Scottish Parliament holds ‘Visual Impairment Cross Party Group’ meetings in which employment issues for this particular group are among the topics discussed; this is encouraging news for people who have lost or are in danger of losing their job as well as for those who are unemployed due to sight loss.

About the author

Cirta Tooth is an optometrist with a special interest in visual impairment. After several years working in community optometry, she is now primarily based in a hospital setting where she works in paediatric, macular, and low vision clinics. She has developed strong relationships with healthcare professionals, local support groups and voluntary organisations. She recently completed postgraduate education in low vision and paediatric optometry. She is involved in teaching optometrists, orthoptists, ophthalmologists, paediatricians, QTVIs, RNIB staff and postgraduate students.

References

- Scottish Government (2010) Registered blind and partially sighted persons, Scotland 2010. Scottish Government https://www2.gov.scot/Publications/2010/10/26094945/0 [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16–64 years), 1999–2000 with 2009–2010. BMJ Open 4 2014;4e004015

- People of Working Age Scotland (2016) RNIB Evidence-based review. https://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/Evidence Based Review Working Age Scotland-B.pdf [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- Hewett R (2015) Investigation of data relating to blind and partially sighted people in the Quarterly Labour Force Survey: October 2011 – September 2014. RNIB. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/education/projects/Newfolder/InvestigationofdatarelatingtoblindandpartiallysightedpeopleintheQuarterlyLabourForceSurvey.pdf [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- Saunders A (2014) The link between sight loss and income. https://www.rnib.org.uk/knowledge-and-research-hub/research-reports/employment-research/sight-loss-earnings [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- Douglas G, Pavey S, Clements B et al (2009) Network 1000: Visually impaired people’s access to employment. Visual Impairment Centre for Teaching and Research, School of Education, University of Birmingham for Vision 2020 UK. Available at: https://www.visionuk.org.uk/network-1000-report-visually-impaired-peoples-access-to-employment/ [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- https://www.pocklington-trust.org.uk/vision-rehabilitation-services-what-is-the-evidence [Accessed 15/06/20]

- Howe GW, Hornberger AP, Weihs K, et al (2012) Higher-order structure in the trajectories of depression and anxiety following sudden involuntary unemployment. J Abnorm Psychol 2012 121(2):325-338

- Cox DJ, Kiernan BD, Schroeder BD, et al. Psychosocial sequelae of visual loss in diabetes. Diabetes Educ 1998 24(4):481-484

- Barton C (2020) Saving statistics: How good are Brits at saving for a rainy day? https://www.finder.com/uk/saving-statistics [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- Lam N and Leat SJ. Barriers to accessing low-vision care: the patient's perspective. Can J Ophthalmol 48(6):458-462

- Lovie-Kitchin JE and Whittaker SG (1999) Interaction between acuity reserve and window size for scrolled reading rates in adults with normal and low vision.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40(4):S34-S34 - UK Government. 2013. Equality Act 2010: guidance. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance [Accessed 21/04/2020]

- Critten V. Expectations and realisations: the employment story of a young man with cerebral palsy. Disability Society 2016 31(4):573-576

- Verhoef, JAC, Bramsen I, Miedema HS, et al. 2014. Development of work participation in young adult with cerebral palsy: A longitudinal study.

J Rehabil Med 2014 46(7):648-655 - Lowe JB, Rubinstein MP (2000) Distance telescopes: A survey of user success. Optom Vis Sci 77(5):260-269

- Macnaughton J (2005) Low Vision Assessment. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK

- Hayeems RZ, Geller G, Finkelstein D, et al. How patients experience progressive loss of visual function: a model of adjustment using qualitative methods. Br J Ophthalmol 2005 89:615–620.

Advertisement

OT CPD See all View all OT CPD

-

Sleep disorders in the eye and related systemic disease

- CPD points: 1

- Closes: 01 Jul 2024

-

Dry eye disease and its impact on everyday wellbeing

- CPD points: 1

- Closes: 01 Jul 2024

-

Repeated low-level red-light therapy: the future of myopia management?

- CPD points: 1

- Closes: 01 Jul 2024