- OT

- Life in practice

- Practitioner stories

- The view from the chair

The cover story

The view from the chair

OT visits optometry practices in Glasgow and London for an on-the-ground view of life in practice

Inside the Mount Florida branch of Munro Optometrists, Frank Munro takes my coat and offers me a cup of tea. There is a Christmas tree nestled in the corner with blue baubles the same colour as the shopfront.

Down the road, past posters that read ‘People make Glasgow,’ a notice in the window of J Lupton Family Butcher gently reminds pedestrians to order their turkey.

Munro tells me that during staff training he encourages new recruits to treat everyone who comes through the practice like a member of their family.

“Never walk past anyone – say hello to them,” Munro shares.

“Show some appreciation for the people who are in the building and you will never go far wrong,” he says.

Munro is one of the founding members of Optometry Scotland. Alongside Donald Cameron and Hal Rollason, Munro spearheaded the introduction of universal eye care in Scotland in April 2006.

On the afternoon I visit Munro, more than 400 miles away in London, Labour MP Marsha de Cordova is presenting the first reading of a bill that calls for a national eye health strategy in England.

If successful, the change would bring England in line with the other three nations of the UK, which already have a single plan overarching the eye care that is delivered in hospitals and optometry practices on a daily basis.

“We rely on our eyes every day, yet we do not give much thought to our eye health until our vision changes,” de Cordova tells parliament.

This complacency about the value of sight is not limited to England, but a gradual shift in the public perception of eye health has occurred since the introduction of universal eye care in Scotland.

Show some appreciation for the people who are in the building and you will never go far wrong

Many patients view a visit to the optometrist as an eye health check rather than simply a place to update a spectacle prescription.

Optometry Scotland chair, Julie Mosgrove, tells me over a video call that 2.2 million people have their eyes examined each year in Scotland, out of a total population of 5.5 million.

“They are coming for preventative reasons and overall health checks as well as with acute problems,” she says.

In England, there were 12 million NHS sight tests over the past year – meaning around 20% of people have an NHS-funded sight test each year, compared to 40% of people in Scotland.

Before the introduction of the new General Ophthalmic Services model in April 2006, Munro believes that cost was the biggest barrier that stopped people getting their eyes checked.

Alongside Cameron and Rollason, Munro worked with the Scottish Government to redesign how eye care was offered in Scotland.

“The Scottish parliament was new, and wanted to make their mark by putting in free dental and eye checks for all. We made the most of that opportunity,” Munro explains.

“We had a blank sheet of paper – how did we see the service going? We were trying to anticipate what the challenges would be,” he shares.

As the plan for eye care was refined and revised, the trio of optometrists went back and forward between their practices and Holyrood for over a year. One day they went in and were told that they had secured the funding.

“That was a special day. Hal and I had a glass of wine and Donald had a cup of tea.”

Progress within Scottish eye care has continued since 2006. Alongside the primary eye examination, funding for supplementary and enhanced supplementary examinations enable optometrists to manage more complex levels of disease.

Munro shares that in England there has been a 40% increase in attendance at outpatient ophthalmology clinics since 2006, while in Scotland there has been a 8% rise over the same period.

“Scotland has more or less flatlined because the care has been retained in the community,” he says.

Around one in three optometrists in Scotland have an independent prescribing (IP) qualification. Funded places are available for the course and every IP optometrist receives a prescription pad on qualification.

Practices are accessible – it is just making sure that people grasp that opportunity

The majority of health boards in Scotland allow for direct electronic referral from optometry practices into secondary care.

Mosgrove explains: “Some practices are able to get feedback back from the hospital through the same system – the systems can talk to each other. Others may send in a referral and then they receive email feedback. On the whole, everyone is working towards electronic referral.”

Closing the gaps

While optometry has advanced in Scotland, as in other parts of the UK, there is room for improvement in reaching under-served communities.

“There is still a lot that we could be doing to promote healthcare – although the uptake is very good across all socioeconomic groups, it could be better,” Mosgrove shares.

“Practices are accessible – it is just making sure that people grasp that opportunity,” she adds.

Munro has six optometry practices within Glasgow. The Mount Florida branch I visit is a suburban practice located on Cathcart Road.

“We are a middle of the road practice,” he tells me.

“A mile down the road one way is very affluent. A mile and a half in the other direction is high deprivation,” Munro shares.

South of Munro’s practice in King’s Park, around one in 10 people are experiencing income deprivation according to data published by the Glasgow Indicators Project. To the north, in Govanhill, the figure is one in four.

Munro has observed a higher proportion of people presenting with advanced pathology from lower income areas – and this has been exacerbated by the pandemic.

“After COVID-19, some of the things we have seen have been awful. People didn’t think we were open, but I was here every day,” he notes.

There are also challenges in letting migrant communities know that eye care is free to access when they are unfamiliar with the Scottish health system.

“If people are not used to being in a healthcare system that is free to access, then they tend to present late with eye problems,” Munro shares.

The next generation

I arrive at Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) as a free breakfast for staff and students is finishing up.

Porridge, baked beans, scrambled eggs, fruit and a cup of tea or coffee are available Monday to Friday at the George Moore restaurant.

“It is hugely popular, there are long queues,” Professor Gunter Loffler tells me.

“It is a recognition from the university that this is a tough time for many students. This is a little way that the university can help,” he says.

We meet at the University’s Vision Centre – a modern, purpose-built facility where the next generation of Scottish optometrists, dispensing opticians and orthoptists hone their skills.

Loffler trained as an optometrist in Germany before coming to the UK and completing a doctorate in visual perception.

He joined the GCU in 2001 and is currently the head of the vision sciences department, which provides training to undergraduate optometry, ophthalmic dispensing and orthoptic students. Students can study towards their Master’s and PhD within the department, while an independent prescribing course is also offered.

We are acutely aware that there are challenges and opportunities awaiting our graduates

GCU was the only provider of optometry training in Scotland until the University of Highlands and Islands (UHI) launched its course in September 2020, with the inaugural intake of UHI students yet to enter the workforce.

“The majority of optometrists in Scotland will have completed their training at GCU. It is not uncommon that I will be walking through a shopping centre and there will be someone who knows me and waves from an optometry practice. It is lovely,” Loffler shares.

Dispensing optician and Vision Centre business manager, Michael Welsh, has shepherded generations of optical students through their training.

“It gives me great pleasure when I receive a prescription where I see the signature at the bottom and think ‘Oh that is one of my former students’,” he said.

Welsh started out as a glazing technician in 1980, crafting spectacle lenses on the second storey of a practice owned by two optometrists. He has since taught their granddaughter.

In Scotland, there are signs in hospitals, GPs and pharmacies telling patients to go to an optometry practice if they have a problem with their eyes – while some GP practices have the same message on their answering machines.

The fact that optometrists have become the first port of call for patients with any eye-related problem has informed the approach that the department takes to developing the next generation of optical professionals.

“We are acutely aware that there are challenges and opportunities awaiting our graduates. We need to provide the foundation for their future career,” Loffler shares.

He sees evidence-based practice as a key skill for the modern optometrist, orthoptist and dispensing optician.

“For that, you need to have an ethos that is underpinned by an understanding of research and the ability to evaluate publications and clinical evidence,” Loffler observes.

Loffler has observed the undergraduate education of optical professionals evolve to the point where the programmes offered by GCU are now “almost unrecognisable” from the courses on offer when he first joined.

“Within optometry, there has been a remarkable shift from screening for disease towards the diagnosis and management of eye conditions,” Loffler says.

In the future, Loffler believes it is conceivable that optometrists in the UK will take on further advanced practice roles.

Perhaps this is a not-too-distant future. When I speak with Munro, he has recently completed training in ocular plastics – learning to remove stitches, for example, when a patient has a tumour removed from an eyelid.

Welsh would like to see employers raise the bar when it comes to the career progression of dispensing opticians.

You need to know the patient. You get people back into practice by having positive relationships with them

The latest data from the General Optical Council reveals that while the number of optometrists in the UK is continuing to climb, dispensing optician numbers have remained relatively static since 2019. Over the same time period, student dispensing numbers have fallen by 25%.

Welsh believes that the value that dispensing opticians bring to practice is not confined to expertise in fitting spectacles.

“I have the family nickname of the ‘The Glasses Man’ – as my late mother-in-law called me – but ophthalmic dispensing is much more than that,” Welsh observes.

“You need to know the patient. You get people back into practice by having positive relationships with them. They don’t just buy a pair of glasses – they buy into who you are and the experience they have,” he says.

Forging connections

I arrive at Specsavers The Forge as the sun is setting. It is four degrees outside – an illuminated ice cream van drives past silently like the ghost of summer.

Clinical director and optometrist, Sufyaan Aslam, takes me through to a room where a ‘World’s Best Dad’ water bottle sits on the desk next to a half empty bottle of Irn Bru and stickers he gives to children after he puts drops in their eyes.

“The days I go home and I think, ‘That was a good day’ are not necessarily because it was a high sales day,” he tells me.

“It is because you had happy patients, a happy team, and everyone left with a smile,” Aslam shares.

Aslam started working on weekends at Specsavers The Forge in 2005, when he was in his third year of university. After completing his studies, he took on a pre-registration position before becoming a full-time optometrist, then supervisor and finally director.

Over the years he has learned the value of listening to patients and understanding where they are coming from.

“If you listen to understand, rather than being on autopilot, then very rarely will you be in a spot where you have missed something or you have an angry patient,” Aslam says.

The practice is Dementia Friends accredited, while practice staff speak a combined total of 15 languages, including Urdu, Mandarin, Arabic, Romanian, Greek and Polish.

Some patients will request to see someone who speaks a specific language, so they are booked in on a day when that team member is working.

“Patients love it. You can almost see their shoulders relax when they talk with someone who speaks their language,” Aslam says.

Data published by the Glasgow Indicators Project shows that four in 10 people in Parkhead are experiencing income deprivation, while half of children live in poverty. Life expectancy for men is 67.6 years and for women it is 75.8.

When headlines about the cost of living are in the news, he observes an effect on the shopping behaviour of people coming through The Forge.

“I have noticed this since the first credit crunch,” Aslam tells me.

“If in the headline it says ‘Universal Credit is getting scrapped,’ suddenly everyone is really concerned and the shopping centre gets quiet. Within a couple of weeks, things go back to normal,” he says.

If you listen to understand, rather than being on autopilot, then very rarely will you be in a spot where you have missed something

Aslam sees higher levels of pathology among patients in Parkhead than he did when he worked days in the wealthier suburbs of West Glasgow. The health of the Parkhead population is affected by a combination of lifestyle and socioeconomic challenges.

He shares with me that the “heart is constantly warmed” at Specsavers The Forge. Aslam recalls a high myope in his 50s receiving his first pair of glasses. The man was deaf and struggled with his vision “but that is how he knew life to be.”

When he put on his new spectacles, for a moment he was stunned before he started jumping up and down, signing applause.

“His happiness was indescribable,” Aslam says.

“Before, he would struggle to see someone signing if they were too far away, but now he could see to the other side of the room,” he adds.

Around one in five patients who come through the practice are children. Dispensing optician, Sundas Afzal, explains that she always includes both the child and parent in the conversation when selecting spectacles.

“If the child feels like they are left out of the decision making, they might not want to wear their glasses or come back to the practice,” she says.

Positive feedback keeps her motivated in her job. She recently fitted a non-verbal adult patient with spectacles, who then immediately left her to go look around outside.

“He couldn’t say anything, but his eyes lit up,” she says.

Aslam, who is IP qualified, appreciates the variety of roles that are available to optometrists now compared to when he first qualified. He recently saw a patient with a several different conditions that required a battery of tests.

“About 20 minutes into the test he said, ‘Do you guys still measure for glasses?’ I said ‘Yes, we do, I promise I am coming to that.’ He was wondering if he was in the right place,” Aslam says.

Team work

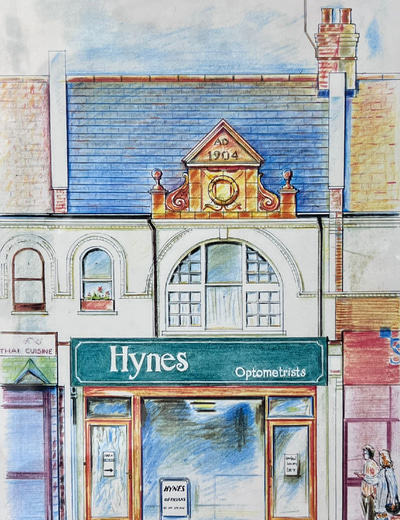

Back in London on a rare snow day, I take the bus past fields blanketed in white and children making a snowman on a traffic island to Hynes Optometrists in Ealing.

Over the decades, estate agents and coffee shops have proliferated on the High Street while Northfield Avenue has said goodbye to independent butchers and the Owl and Pussycat children’s bookshop.

Hynes Optometrists has remained a constant, offering slices of home baked orange polenta cake, Victoria sponge and tea at regular fundraising coffee mornings.

“Some of our patients live on their own and they look forward to these coffee mornings. Joy gets out her antique teacups,” practice manager and dispensing optician, Linda Menezes, tells me.

If it happens to be a patient’s birthday when they come through the practice, the staff will sing to them.

“We want to make them feel special for making the decision to come to us,” Menezes says.

“It is about treating them as a special person, because that is exactly what they are,” Joy Hynes adds.

During the course of the interview, it becomes clear that Menezes and Hynes have the kind of friendship, formed over decades, that sees them finish each others’ sentences.

I am the boss, but we work with each other and for each other

In the past, Menezes was a music teacher. Hynes had a vacancy for a dispensing optician and convinced her friend to study for the qualification by correspondence.

Menezes believes that a stable staff base helps to build trust and loyalty with patients.

“When the patients come in, they see the same faces. They are very happy – there is that continuity of care,” she says.

Stories about Hynes father, who died when she was a young girl, have shaped her approach to working life. Hynes shares that his philosophy was to treat all his employees fairly, respectfully and with kindness in the knowledge that they would respond in kind.

“What is really important is that we work as a team. I am the boss, but we work with each other and for each other,” she says.

Bespoke service

Next to a thin strip of ice surrounded by a picket fence (‘This way to traditional Bavarian curling’), coins glint beneath the frozen surface of Sloane Square’s fountain.

At Tom Davies Bespoke Opticians, beside a black and white portrait of the eponymous designer, a video details the process of making bespoke frames.

Store manager, Courtney Smith, shares that customers choose a template frame and colour before head, bridge and ear width is measured. An eyewear design is then created using CAD software to translate the customer’s measurements into their own unique pair of frames, before the designs are sent for manufacture at Tom Davies’ West London factory.

Using i.scription technology (marketed by Zeiss as a “personal vision fingerprint”) the lenses within a Tom Davies frame can also be tailored to the individual.

With an hour set aside for each consultation, there is time to talk through the specific requirements of each customer.

“I always keep in my mind that this is a special moment for this person,” optometrist, Tuija Kankaanpaa, shares.

Many of the practice’s customers live in the local area, drawn to the practice on the recommendation of family members and friends. There are also tourists who stop by on the way to visiting King’s Road and Harrods, and overseas residents with holiday apartments in London who time their appointments for when they are in the city.

Sloane Square sits within the Kensington and Chelsea borough, one of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in London. Life expectancy at birth is 83.9 years for men and 87 years for women.

On the store floor of Tom Davies, prices are absent from the rows of frames on display.

Kankaanpaa notes that cost is far from the customer’s mind when they see the quality of the final product. Sometimes customers are reluctant to part with their frames when their prescription changes, so the team will replace the lenses before taking care of the frame – polishing acetate and nourishing horn frames with cream.

Smith shares that a good pair of frames can have a transformative impact.

“It can boost your confidence and change your life,” he says.

Smith adds that there is a family feel to the practice, with every customer given a warm welcome.

“I believe in treating customers in a way in which you would like to be treated. When I go somewhere I would like to be given good service from start to finish. I do the same with every customer who comes through the door,” he says.

Royal treatment

In August 2022, there were more than 800 royal warrant holders in the UK – covering goods and services from flags, church robes, candles and champagne, to asbestos removal and equine dental services.

Roger Pope Opticians in Marylebone holds two royal warrants for dispensing optician services to the royal household.

The practice was dispensing-only for a decade after opening in 1987. Optometrists were recruited to Roger Pope Opticians after the Harley Street consultants who had previously provided prescriptions stopped performing refractions.

With more than five decades of experience as a dispensing optician, Pope can look at someone who has walked into the store, mentally run through a catalogue of 800 frames and hopefully come up with a pair that are a good match.

“You can self-select, but on the whole people expect us to guide them through the whole process of choosing their spectacles,” Pope says.

Pope says that he is often working with customers who are at the top of their professions, and they demand the best from him in return.

“You are not always looking at the cost aspect. If you say to someone, ‘I think this lens is the best lens for this prescription,’ they will often have the means to pay for that. It gives you a wider scope,” he shares.

It’s no good to put a name on something if it doesn’t match the quality

The range of lenses and coatings has expanded dramatically since Pope qualified in 1971. When he first started working, before varifocals and plastic lenses, Pope would select from a narrow range of glass bifocal NHS lenses.

“The world of lenses today is phenomenal. I think there are lenses out there to suit anybody, but you have got to listen to what their needs are,” he says.

The practice does small repairs for spectacle wearers – they do not need to be existing customers. Pope notes that people will often come back for frames after a good experience with a repair.

The practice will not sell poor quality frames, even if it is from a designer brand.

“If it doesn’t meet certain criteria, we won’t stock it. It’s no good to put a name on something if it doesn’t match the quality,” he says.

At the age of 76, Pope now comes into practice two days a week. But he is supported by a team that has decades of combined experience fitting spectacles for the varied community that lives in the West End.

“Everybody knows people by name when they come in,” Pope says.

Pope believes dispensing opticians have an important role to play in translating what has been found in the consulting room into a well-fitting pair of spectacles with good quality lenses.

“I think dispensing optics does get pushed to the back. I think it is vital,” he says.

He will always shake the hand of new customers and walk them to the door when they leave.

“We would never let them wander off. I think that last impression can be as important as the first,” he says.

Advertisement

Comments (0)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in