- OT

- Industry

- High Street

- Sink or swim

The cover story

Sink or swim

OT talks with eye care professionals in Wales about how the profession can work together to create a sustainable future

23 August 2022

Optometrist Ceri Probert lives next to an ocean that is grasping at the land. In Aberystwyth, climate change can be seen in clouds casting shadows dark as squid ink across the ocean, rainfall lifting sandwich boards and road cones from the pavement, the ocean spray battering colourful townhouses.

“We regularly get floods on the seafront. Our practice is up on a hill, so we are relatively safe, but the businesses on the front tend to take a hammering,” Probert told OT.

An hour’s drive north, residents of Fairbourne have been told by Gwynedd Council that the low-lying town will not be defended from sea level rises beyond 2054. Roads, shops and infrastructure will be dismantled as the village returns to marshland, while the village’s 700 inhabitants will be forced to find a new place to call home.

With climate change on his doorstep, Probert is passionate about the role that optometrists have to play in embracing a sustainable future.

“We are only a small cog in the grand scheme of things, but I think if, as an industry, all of us make little changes then we can be part of a larger change,” he emphasised.

Alongside his wife, Probert is co-director of three optometry practices in mid-Wales –Aberystwyth, Aberaeron and Machynlleth.

The couple had been considering how they could become more sustainable from a personal perspective but realised that a significant component of their environmental footprint is outside of home.

“Really our biggest impact is the business – we needed to start changing that as well,” he said.

A framework for change

Probert and Williams was one of three optometry practices that signed up to the Greener Primary Care Wales Framework and Awards pilot.

The Public Health Wales initiative involves optometrists, GPs, pharmacists and dentists signing up to improve their sustainability across a number of categories.

At the end of the year, the evidence primary care contractors have submitted is audited and they are awarded bronze, silver or gold status depending on how many actions they have completed.

Through the pilot, Probert created an ethical and environmental sourcing document as well as a 10-page list of actions to improve the sustainability of his business – each with a cost and deadline.

“It runs right from changing the lightbulbs over to LEDs to calculating our carbon footprint,” Probert shared.

“We have looked at our general procurement – for example office supplies, tea and coffee – and have examined them from a sustainability perspective,” he added.

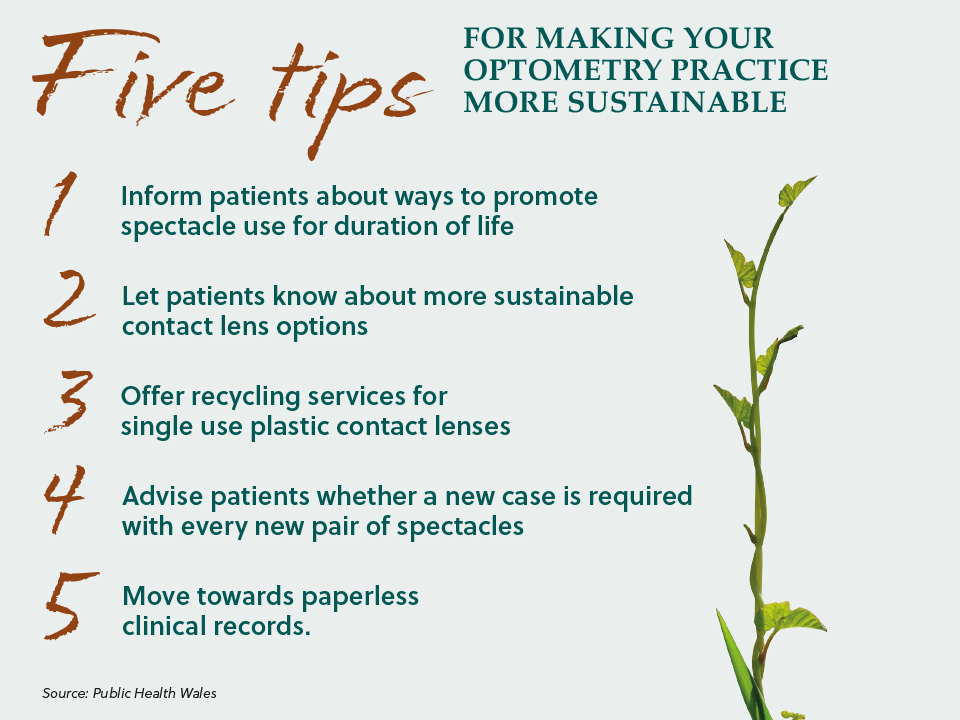

Patients are not automatically given a new spectacle case with each set of frames. They can instead choose a donation to an environmental charity in lieu of a new case.

Small steps

In Cardiff, signing up to the Greener Primary Care Wales pilot has inspired optometrist Bethan Roderick to create a sustainability ‘wish list’ – from installing solar panels to cultivating a bee-friendly green roof with grass and flowers.

She plans to petition the council for an electric car charging point in the car park behind Canton Optical.

“Every time an idea comes to me, I will jot it down,” Roderick said.

Growing up in suburban Hertfordshire, a trip to the countryside was an all-day activity for Roderick.

I don’t want to lose this lush green land which we live in

After she moved to Cardiff in 2000, Roderick gained a new appreciation for the wilderness in easy reach of her new home.

“I don’t want to lose this lush green land which we live in,” Roderick observed.

Roderick has replaced the disposable ballpoint pens at her practice with metal refillable pens, while she personally uses a fountain pen with a bottle of ink to write records. This is the most common way that the topic of sustainability will come up with patients.

“The conversation usually starts when the patient notices I’m using a fountain pen and says ‘Oh, I haven’t seen one of those in years.’ And then I will explain why I am using it,” she said.

A drive to reduce the amount of plastic in Roderick’s life saw her learn how to make her own soap.

“I was always asking myself ‘Do I really need to have this plastic in my life?’,” she shared.

Like Probert, Roderick realised the contrast between the steps she was taking to become more sustainable at home and the impact of her business.

In order to reduce the footprint of her practice, she switched to a green energy supplier and changed the light fittings to LEDs.

Roderick acknowledges that there is potential to become overwhelmed when trying to become more sustainable.

Turning to barriers to sustainability within the profession, Roderick pointed to the high proportion of products within optometry that contain plastic.

She added that because of the business model within optometry, there is a drive to sell glasses in order to cover overheads.

“Our entire profession is driving this need for new spectacles, new frames and new lenses, so that we can pay the bills and pay the wages,” Roderick observed.

“I think if we could divorce healthcare from the sales side of the profession, that would make it a lot easier for practices to be more sustainable,” she said.

Over the years, Roderick has been pleased to observe a focus on sustainability moving into the mainstream.

She would like to see environmental considerations become integral to business – rather than something that is confined to the home or learned about at school.

“It’s getting into the mindset where sustainability is not a hobby along the lines of being interested in knitting – it is something that we all have a responsibility to contribute to because we all live on the same planet,” she said.

Storm warning

While rainfall in Wales creates verdant scenery, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events has taken a toll on its towns and cities.

A succession of storms in February 2020 left 3130 properties flooded across Wales and caused £81 million in damage.

During Storm Dennis, the River Taff reached its highest level at Pontypridd since records began in 1968. At peak flow, the river would have filled an Olympic swimming pool in just over three seconds.

North of Cardiff, the Nant yr Ysfa rain gauge recorded 72% of an entire month’s rainfall within a single day.

“It is an unwelcome reminder of the power of nature, and evidence from climate scientists suggests that we will see more extreme weather events in the future,” Natural Resources Wales (NRW) emphasised in a report assessing the damage.

The report noted that flooding has the potential to have long-term impacts on communities – both physically and mentally.

“The flooding events experienced across large parts of Wales in February 2020 were devastating for many communities, and in many cases, it will take months, if not years, to recover,” NRW emphasised.

As with other effects of climate change, it is the often the most deprived communities that take the longest to recover from flooding.

In Wales – where those in the least deprived areas are expected to have 19 more years of healthy life than those in the most deprived areas – existing societal divides have the potential to be exacerbated by the impact of climate change.

Sustainability for all

Growing up in north Wales, optometrist Tim Morgan observed this disparity in his own community.

“There were huge differences within the area of half a mile,” he said.

“I have always felt that is incredibly unfair. When you look across the world, you realise that where you are born has an inexcusably huge impact on your expectations in life,” Morgan observed.

Morgan shared with OT that sustainability is about looking after others as well as looking after the environment.

“We need to consider the health of future generations as well as the health of the patients who are in the chair immediately in front of us. This is integral to the responsibilities of a healthcare professional,” he said.

In August 2021, the Welsh Optometric Committee became the first optical body within the UK to declare a climate emergency.

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act, passed in 2015, creates a legal obligation to consider the environmental impact when making policy decisions.

“There’s a lot of appetite to make change. In Wales, in particular, the conditions are right,” Morgan said.

Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, Sophie Howe, highlighted the importance of making a connection between climate change and the health of communities.It's not as simple as saying sustainability is a luxury. We need to challenge that instinct

“For our future generations, climate change is one of the biggest threats to their health and livelihoods,” she said.

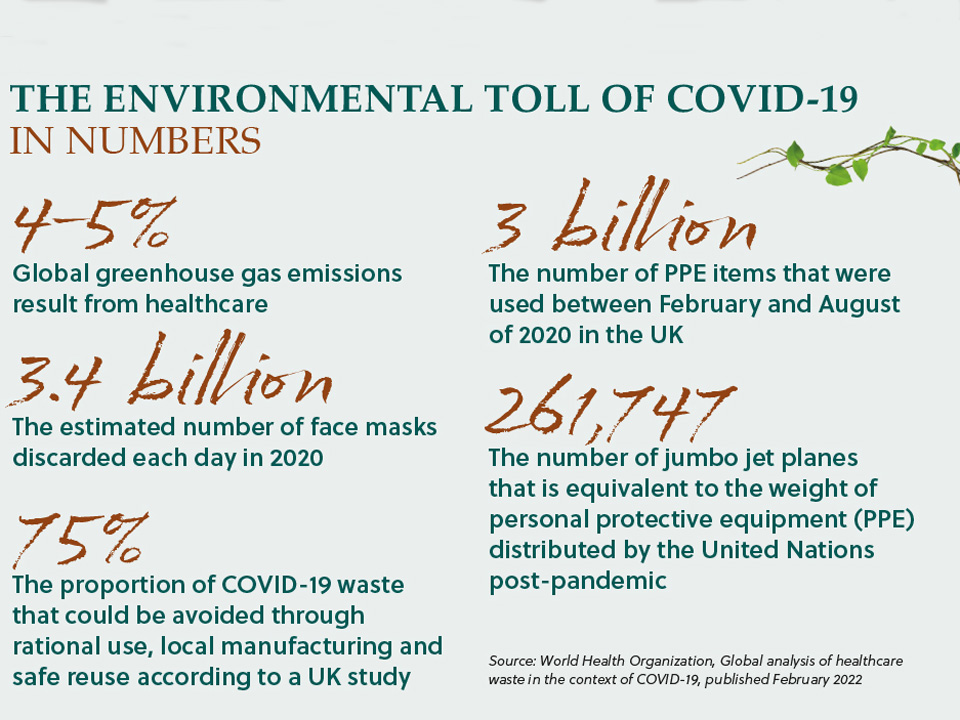

“However, we know that our healthcare systems are responsible for high emissions and high levels of waste. And not just our big hospitals, but our community pharmacies, our dental and general practices, and optometry too,” Howe observed.

Morgan, who also took part in the Greener Primary Care Wales pilot, has created a sustainability plan for his practice with seven chapters – covering topics from procurement and waste to public engagement, auditing and research.

“It is a structured way of making improvements,” he shared.

He emphasised the importance of involving the whole team in sustainability initiatives – as each member will have unique insight on how processes can be improved.

“It is not about the principal optometrist telling everyone else what to do. This is the time to innovate. Everyone can – and should – be involved,” he said.

Morgan highlighted that there can be an assumption that improving a practice’s sustainability is expensive – but some of the changes he has introduced in his own practice have reduced his overheads.

For example, posting items less often has had an environmental benefit while also limiting costs.

Morgan, who describes himself as a “pragmatic hippy,” shared that sustainability is an integral part of his business.

“From the most basic things to how we structure the clinics and how we encourage staff to travel – sustainability is part of every process. It isn’t a case of – on Monday we are sustainable, then we forget about it,” he said.

Although Morgan is passionate about action on climate change, he does not believe that negative conversations on the topic are helpful as there is a risk of numbing people into inaction.

Instead, he encourages people to consider what they can do to create a world they want to live in.

“We are all coming at this at our own pace. I acknowledge that we are not perfect but what I hope is that today is the worst that we ever are and tomorrow is a bit better,” he said.

What the UK can learn from low-income countries

Ophthalmologist Dr John Buchan is the programme director of the MSc for Public Health in Eye Care run by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

In June, Buchan and colleagues published a scoping review in The Lancet Planetary Health assessing the extent of existing research on the sustainability of eye care services.

Buchan shared with OT that the current way of operating within eye care is not sustainable.

“We can’t continue at the scale that we are: pumping hydrocarbons from under the ground and turning them into plastics which we then use for a few seconds in some healthcare intervention, then throw away,” he said.

Buchan highlighted that standard healthcare practice in high-income countries, such as the UK, is very different to that in low-income countries.

For example, in India and most of sub-Saharan Africa, rather than throwing away equipment at the end of the operation, it will be sterilised and then used on the next patient.

Gloves are washed and covered in 100% alcohol between procedures.

“That might sound countercultural for us, but because there is one hospital system in India that is doing the same number of cataract operations as the whole NHS in England, this is their practice,” Buchan shared.

He added that despite these differences in practice, infection rates are no higher than within the UK.

The disease was passed on through neural tissue, with research determining that sterilisation was ineffective in killing the prions responsible for disease transmission.

“There became an environment within healthcare where instruments that were used on certain parts of the anatomy were thrown away,” Buchan shared.

“In some eye hospitals, almost everything you use for a cataract operation will be thrown away and then incinerated,” he said.

More broadly speaking, Buchan highlighted that a “disposable culture” has evolved in the UK over the past two decades.

“The link between what things cost and what they are worth has broken down because of the asymmetry in wages around the world,” he said.

“For instance, metal is dug out of the ground and made into forceps, often in Pakistan, and they are hand-finished in a factory, sterilised, put into packaging and shipped around the world. Yet they retail for a few pounds,” Buchan highlighted.

Within the UK, ophthalmology accounts for 9% of outpatient activity. The volume of activity is expected to increase as the population ages.

Buchan emphasised that in the future both ophthalmologists and optometrists will have to deliver more care within the confines of limited funding and equipment.

“If you have to deliver more care with the same resource, you have to change the way you behave. All of us have to find lighter ways of working – that means financially and environmentally lighter,” he said.

In 2013, researchers from Cardiff university found that the carbon dioxide produced by a single cataract operation was 181kg.

The researchers estimated that the carbon burden of all cataract surgeries in England over a single year was 63,000 tonnes – or 31,500 return flights from London to New York.

The link between what things cost and what they are worth has broken down

Buchan believes that clinicians should reassess their approach to risk, taking environmental considerations into account.

While the individual patient in front of a clinician may not be put at risk by wasteful behaviour, the environmental legacy creates broader concerns.

“We need to challenge this assumption that wasteful behaviour is somehow safer for patients. You are putting people at risk by using up the world’s finite resources,” he said.

Buchan highlighted the dissonance he sees in the approach to risk within hospitals when compared to what happens outside their doors.

On the journey to hospital, that patient may have leaned their head on the window pane or touched their face after opening a door.

“I don’t think using a felt tip pen on consecutive patients is really more of a risk than any activity in normal life,” he said.

“Yes, there are possible transmissible diseases out there – but the way we throw some things away is just not sensible,” he said.

Buchan would like to see sustainability become an integral component of research design – so alongside the effectiveness of a given treatment or pathway, the environmental impact would also be considered.

Buchan shared his belief that clinicians have a “moral compunction” to act in the interests of future generations.

There is an unequal impact to climate change – with those in countries with higher temperatures and fewer resources suffering the greatest effects.

“Within the UK, we could continue to behave as we are and it wouldn’t affect me in my lifetime, but there would be other people in other countries and in future generations who would be profoundly affected if we don’t do our bit,” he said.

“Climate change affects us all”

Angharad Wooldridge, from Public Health Wales, discusses the Greener Primary Care Wales Framework and Award Scheme

How does the framework and award scheme work?

Any primary care contractor in Wales (optometric practices, primary care dental practices, community pharmacies and general practices) can register for free online. The digital framework contains a number of categories including procurement, waste and healthy behaviours. Each category contains a mixture of clinical and non-clinical actions for practices to self-select and attempt at their own pace. Further information is provided alongside each action to support practices in completing their chosen actions. Once an action has been implemented, evidence in the form of commentary or supporting documentation is uploaded to the framework to demonstrate completion. Each completed action equals one point and as the number of points increases so does the level of award achieved e.g. eight points is recognised with a bronze award. At the end of each annual cycle, the evidence submitted by a practice will be audited by trained university students. This year the framework will close for new evidence submissions on 28 October and the audits will take place on 16 November.

What types of sustainability measures have primary care contractors made during the pilot phase?

Initiatives ranged from calculating a practice’s carbon footprint to encouraging safe inhaler disposal. In relation to the three optometric practices that participated in the pilot, they took on a broad range of actions such as changing to a more environmentally sustainable supplier for their printer and toner cartridges and a local supplier for office supplies; switching to Fairtrade tea and coffee; promoting a ‘spectacles for life’ approach and removing a reglazing fee; and routinely advising patients about whether a new case is required when new spectacles are purchased, to name a few.

Why is sustainability an issue you are passionate about?

Climate change affects us all, but it disproportionately impacts those who are already at the most disadvantage in our society. By working together we can make a positive impact on the future of our planet and safeguard the health and wellbeing of our future generations. We strongly believe that healthcare professionals have a personal, professional and organisational duty to act

The Greener Primary Care Framework and Award Scheme has completed the pilot phase and all optometry practices in Wales are now eligible to sign up for free online: www.greenimpact.org.uk/greenerprimarycarewales.

Those interested in finding out more can contact: [email protected] or visit www.primarycareone.nhs.wales/topics1/greener-primary-care/

Image credit: Jason Thomas

Advertisement

Comments (1)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in

Anonymous04 January 2023

The AOP talking about sustainability and the environment, when they send out 100 page Optometry in Practice full of Specsavers advertising to every member several times a year, which goes straight into the recycle bin in most cases. Not the best use of the earth's precious resources.

Report Like 228