- OT

- Professional support

- Health services

- Timely triage

The cover story

Timely triage

The strain of the pandemic on primary and secondary care has brought to the fore the importance of seeing patients in the right place at the right time. OT explores the art of triage

23 December 2021

In the early months of the pandemic, when routine eye care appointments were suspended and practices operated on a skeleton staff, across the country optometrists faced a daily conundrum.

Often sitting in a room with only a phone for company, eye care professionals mulled over whether the patient they had just spoken to needed to be in practice or whether they could safely wait at home.

“It was balancing the risk of someone having a significant problem with their eyes and the general risk of seeing someone face-to-face with a transmissible disease in the community,” optometrist and AOP clinical adviser Kevin Wallace shared with OT.

While statistics for England have not yet been released, data from Northern Ireland reveals that the number of General Ophthalmic Services sight tests performed in the year following the pandemic dropped by 34%.

Wallace shared that triage skills refined during the pandemic are still being applied following the recommencement of routine appointments. “From speaking to other practices, I know most people are busy because we have a backlog of routine tests to get through. We are still having to be fairly choosy about how we appoint people,” he said. Wallace emphasised that triage processes within optometry practices have improved during the pandemic.

“It would be good if that could have happened without a devastating worldwide event, but we have become much more used to deciding, one, if a patient requires to be seen and, two, how urgently they need to be seen,” Wallace shared.

Prioritising training

At Wallace’s Edinburgh practice, all staff receive training in triage as a priority when they start while a triage form with key questions is used by staff appointing patients.

The questions on the form have been adapted and honed over the decade since the resource was introduced.

“It’s a cycle of audit, changing the system and then auditing it again to see if it needs to be tweaked further. This ensures that the process becomes more efficient with time and that the important things are prioritised and less important issues do not take up valuable emergency appointments,” Wallace said.

He emphasised that a hallmark of an effective triage system is that it is led by the non-clinical staff.

“If your triage system requires someone to knock on my door every time a patient phones, it doesn’t work. It’s not effective. You should be able to work out 99% of them by asking straightforward questions,” Wallace highlighted.

During the pandemic, hen only emergency cases were seen in secondary care, independent prescribing optometrist Stanley Keys worked in casualty clinics at Raigmore Hospital in Inverness as well as for a triage line staffed by optometrists and ophthalmic nurses.

“We were helping the nurses to do the triaging and to keep it as tight as possible – only seeing patients who we really thought needed to be seen,” he said.

Keys’ experience on the triage line prompted him to develop a triage training course for ophthalmic nurses and a triage guide.

“The COVID-19 pandemic, and the work that we did with our nurses locally, made me feel as though there is an area where training would be beneficial and worth developing,” Keys shared.

After a successful pilot over the summer, the first courses in October and November were fully subscribed, while an NHS trust in England has commissioned a bespoke course for a group of 14 nurses.

Since publication, the guide has been sent to 60 practices in all four nations of the UK. Keys has also received interest from optometry practices in Australia.

“It’s quite a nice thought that something you have produced is going to the other side of the world to help a practice,” he noted.

Keys shared that the content of the triage guide provides useful guidance for all staff who encounter emergency eye conditions.

“It will be equally useful for ophthalmic nurses working in hospital as it will be for staff in optometry practices and even GP clinics,” he said.

A team effort

Like Wallace, Keys emphasised the importance of the whole practice team understanding the importance of triage.

“You can have the best clinicians in the world with the best knowledge and experience, but actually if you don’t have a good front of house team booking the appropriate patients in, controlling the diary and ensuring that high priority cases are getting through, then it is almost irrelevant if you have super clinicians,” he said.

Working in a hospital environment, Keys knows firsthand the importance of patients being directed to receive care in the appropriate environment at the right time.

He added that in each casualty clinic, there might be one patient with complex needs who requires input from a range of disciplines.

“They can be time-consuming but these are the patients who need to be thoroughly investigated,” Keys shared.

“You don’t want to have your diary clogged up with cases that don’t need to be seen that day. The heart of it is really the patient – their needs and making sure that those who really need the urgent care are seen as a priority,” he said.

Shared care

As the pandemic has exacerbated pressure on secondary care and waiting lists for elective care have grown to record levels, more NHS trusts are exploring the potential for primary care to take on services traditionally offered in hospital.

An announcement by the Scottish Government in September 2020 detailed the provision of a £3 million funding pool for initiatives that see community optometrists support the hospital eye service.

Optometrist, Optometry Scotland member and co-owner of McFarlane and Nicol’s Ltd, Richard Spruce, is involved in a shared care scheme that has been rolled out as a result of the funding in the Forth Valley.

Five practices in the area introduced glaucoma clinics in October as part of measures to ease the hospital backlog.

Speaking with OT shortly before the launch of the glaucoma clinic at his practice, Spruce shared that he had received positive feedback on a similar shared care system in the past.

“The patients who I saw in the Selkirk were very happy not to have to go to the hospital,” he said.

“It is a nice service – to see them on their doorstep rather than for the patient having to trek over to hospital,” Spruce added.

Through the new initiative, Spruce has blocked out one morning each week to see six patients from the hospital eye service.

In advance of their first meeting, Spruce is sent the last clinic letter for each patient setting out key information about their history and management through the electronic patient record software, OpenEyes.

He then performs tests set out in the standard operating procedure and records them on OpenEyes.

If he has any concerns about patients seen through the service, Spruce can flag these with the hospital eye service.

“Most of the cases are stable – the consultants are fairly happy with their eye pressure and they are not expecting things to go haywire,” he said.

Spruce shared that on some of the records he has seen patients were told a year or 18 months ago that they needed to be seen within six months.

“These patients have not been seen and they need to be. If we don’t see them there will be more pressure on the hospital and it just snowballs,” he said.

As well as easing hospital waiting lists, the shared scheme has potential to foster strong relationships between community optometry and ophthalmology.

Spruce shared that his practice has built up a good relationship with the hospital over time, but the shared care initiative will strengthen this.

“You do get to know the consultants more. They are not just a name, they become a face and a person. They get to know us and trust us – they know we are reliable and give them good data,” he said.

Spruce noted that having standard operating procedures meant that the service could be rolled out to other areas in the future.

“This is something could be easily expanded going forward – they have the foundations there,” he said.

Calculating the value of High Street optometry

While most optometrists would agree that more patients receiving eye care on the High Street is a good thing, the data illustrating why this is the case can be challenging to pin down.

His research, Community Eye Care and GP or Hospital Referrals in Scotland: A Tale of Two Stories, analysed the relationship between High Street eye examinations and referrals to a GP practice or hospital using health board data collected between 2011 and 2018 in Scotland.

“The findings of this paper highlight the effectiveness of community eye care services delivered by optometrists,” Zangelidis said.

His research found that a 5% increase in primary examinations within optometry practices was associated with a 10% drop in referrals.

“Eye conditions are treated at the community level and not referred to a GP or hospital,” he shared.

Conversely, an increase in supplementary examinations were linked to an increase in referrals.

Zangelidis highlighted this finding supports the preventative role of High Street optometry, as supplementary examinations often detect previously undiagnosed, asymptomatic conditions.

“In the absence of those eye examinations, what we anticipate is that these health conditions would remain undiagnosed for a longer period of time. Early detection of these health conditions through a supplementary eye examination can potentially save NHS resources in the long-term,” he said.

Zangelidis noted that while there are differences in the provision of eye care in Scotland, other UK nations can learn lessons from the Scottish system.

Previous research by Zangelidis investigated the impact of accessible eye care on rates of hypertension in Scotland.

He found that as the uptake of eye examinations increased following 2006 reforms that made a comprehensive eye examination free of charge, more cases of hypertension were detected.

“That provides evidence that an eye examination is not only about your sight but about your general health. If those cases are not detected on time, they can lead to a deterioration of the patient’s health, which makes treatment more expensive and more complicated,” Zangelidis observed.

He noted that a larger proportion of individuals from affluent households took up the offer of free eye examinations following the 2006 reforms in Scotland.

Zangelidis shared that in the future he would like to see a range of interventions piloted that aim to increase the number of people who are getting their eyes tested – particularly from lower socioeconomic groups.

“There is mounting evidence that people should be strongly encouraged to have their eyes tested on a regular basis. This is important for the individual and from a public health perspective,” he said.

Zangelidis observed that during the pandemic there has been a significant disruption to healthcare, including the temporary suspension of eye care.

“What we have seen is that even when eye examinations resumed, priority was given to emergency cases and many examinations were further delayed,” he shared.

Some patients remained reluctant to have their eyes tested even when their vision became worse, Zangelidis added.

“The fact that we saw fewer referrals across the NHS does not suggest that people’s health has improved, what that suggests is that there are cases that have not been seen. We need to be very careful when considering any future restrictions on healthcare services,” he said.

Remote consultations

One way that optical professionals have worked to streamline their triage process and use resources effectively during the pandemic is to use digital solutions.

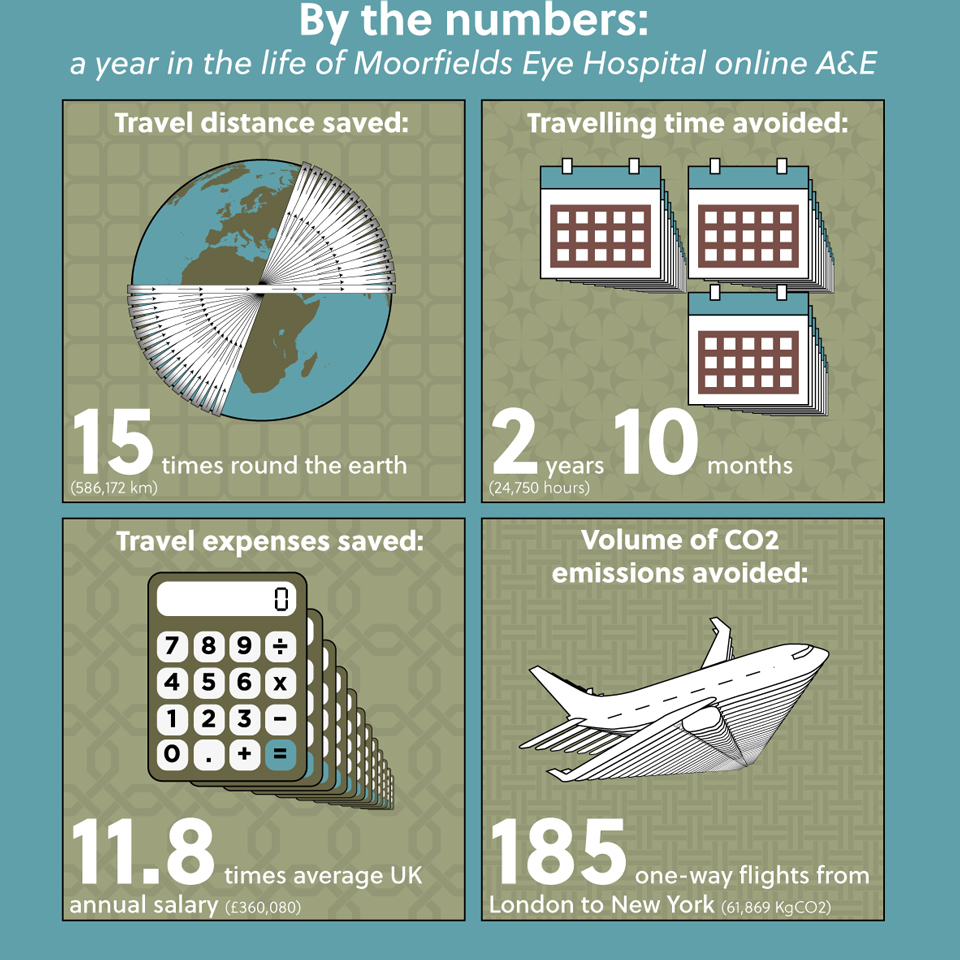

Since then, the service has accounted for more than 26,000 consultations – with only 22% of patients requiring a face-to-face A&E appointment.

On average, each patient avoided a journey of 41 kilometres and travel costs of £25.07.

Service director for Moorfields Eye Hospital A&E/Urgent Care, Dr Gordon Hay, highlighted that optometrists have been involved in offering the service since the beginning of the pandemic.

“At present we have five optometrists working in the emergency department, either seeing patients face-to-face or on the virtual platform,” he said.

Hay noted that many Moorfields Eye Hospital patients live some distance from London.

“These patients did not want to leave home during the worst part of the pandemic, and we were keen to reduce the need for them to come to London when the infection rate was so high,” he said.

“Ultimately, given that so many people have risk factors for COVID-19 or are immunosuppressed, it’s been hugely beneficial to be able to triage patients remotely and get the right care from the right team at the right time,” Hay emphasised.

As well as benefitting patients, the service enabled staff who were shielding or unable to work with patients face-to-face to continue working.

“We had staff on maternity leave who wanted to contribute, and staff who were stuck in other parts of Europe unable to get back due to airline difficulties,” Hay elaborated.

Hay shared that the range of conditions that clinicians have seen through the Attend Anywhere platform has included corneal abrasions, relapses of uveitis, visual loss and pain.

“Virtually everything that would be presented to face-to-face A&E also has a presence on the platform,” he said.

Referral tips

The pandemic has heightened the need for hospital referrals to be carefully considered by optometrists.

Hay shared with OT that a direct dial line for community optometrists to receive advice and guidance has been established by Moorfields Eye Hospital.

“I think one of the main problems we’ve had in the past is how difficult it has been for optometrists to get advice from their local eye unit. Since the start of the pandemic, many units have made it far easier for optometrists to seek advice and guidance from their local unit,” Hay said.

Community optometrists in the Moorfields catchment area interested in the direct dial line can make contact with systems partnership manager, Zain Mohammed, to learn more.

Hay encouraged optometrists to collect a full history and background information from the patient before contacting the hospital.

“My top tip for optometrists is to get all of the information together before you pick up the phone so that you can give us a clear and concise narrative when you speak to the ophthalmologist,” he said.

Hay emphasised that the “overwhelming majority” of optometrists are fully aware of what is and what is not a same-day emergency.

“There’s always a difference between what ophthalmologists think is a same-day emergency versus what optometrists think is a same-day emergency, but having made it so easy for community optometrists to get advice and guidance, we’re now seeing more appropriate referrals into specialist clinics and a reduction in the number of unnecessary referrals to A&E,” he shared.

From optometry to ophthalmology

Dr Elizabeth Hill is someone who has a unique perspective on triage, with experience both receiving cases for triage as an ophthalmologist and referring patients to hospital as a High Street optometrist.

She currently works as a consultant ophthalmologist and urgent care lead at County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust.

Hill initially trained as an optometrist before starting a medical degree at the age of 25, funding her training through locum work as an optometrist.

Part of Hill’s job is to triage new referrals coming in from GPs and optometrists and appoint those patients appropriately.

When asked for her tips on referrals, Hill shared that when she receives a referral from an optometrist, she needs enough information to make a clinical decision that is safe.

She values legible, succinct referrals with relevant medical and ophthalmic history, as well as what the optometrist has found during the examination.

“What I need to be able to do as an ophthalmologist is look at your referral and decide when to see the patient,” Hill shared.

“Look at the referral and think ‘Can the ophthalmologist triage this? Is there enough information there to make a decision without calling the patient?’,” she added.

As a former optometrist, Hill has an appreciation for the challenges that her colleagues working in the community face when they are deciding whether to refer a patient to hospital.

She shared that as an ophthalmologist working in urgent care, she sees pathology all day, every day.

“I think sometimes ophthalmologists don’t appreciate that optometrists see ‘normal’ most of the time with a scattering of pathology,” Hill observed.

In contrast to practices that may only have one optometrist working, Hill shared that she works in a department where there are usually three or four consultant ophthalmologists working at the same time.

“You can pop next door and ask someone if you are unsure,” Hill shared.

She has access to the latest technology working in hospital and the ability to bring patients back into the clinic for a follow up examination.

“I have said to juniors that they have to understand what it is like for optometrists at the front line,” she said.

Hill noted that a further challenge for many optometrists is a lack of feedback from the hospital eye service.

This is something that she is endeavouring to establish within her own unit.

“It would be nice to be able to feedback to optometrists and say ‘Yes, that was a really good spot’ and ‘That wasn’t something to worry about’,” she said.

“Otherwise people just do the same thing again and again. You only get confidence by knowing what has happened to your case and getting feedback,” Hill emphasised.

Reflecting on what she wished she had known as an optometrist, she shared that not all pathology is an emergency.

“Just because you identify something in a patient’s eye, the alarm bells don’t need to ring. It is much better that people are seen at the right place at the right time with the right people there,” Hill shared.

Elizabeth’s referral checklist

- Legible?

- Brief? Could use a bullet point list

- Date, patient and optometrist details, visual acuity

- Relevant medical and ophthalmic history

- Reason for the visit – routine or because of a problem?

She cautioned optometrists against telling patients how soon they should be seen within the hospital eye service.

“Sometimes an optometrist will feel that something needs to be seen urgently and an ophthalmologist may disagree,” Hill said.

“Once the patient has been told that they have a sight-threatening emergency condition and the ophthalmology department say they will not see it for a month – that creates a lot of panic,” she added

In the past, she has seen children who were told by their optometrist that they had a tumour when they did not.

“In terms of diagnosis, you can put ‘This could be x’ but it can be risky for an optometrist to make a definitive diagnosis and then tell the patient what is going to happen,” Hill shared.

Optometrists should consider what action they would like the hospital eye service to take with the patient.

For example, many units have long waiting lists for patients with suspect glaucoma.

“If you have someone in front of you with normal vision, normal fields, normal pressures and their OCT scan makes you think ‘Oh well it could be predicting glaucoma in seven years,’ consider whether that referral needs to be in the hospital eye service,” Hill shared.

“I am not suggesting that optometrists take risks and sit on pathology, but my question is what are you wanting the hospital eye service to see the patient for?” she said.

A rewarding role

Working as an ophthalmologist, Hill shared that a rewarding part of her job is providing patients with a high standard of care.

“I love my job and I love working with the patients,” she shared.

She also enjoys the challenges of operating. For example, when performing cataract surgery, the anterior chamber is only around 2.3mm.

“It is a beautiful operation. You operate and 15 to 20 minutes later you have made a big difference to someone’s life,” Hill shared.

The pandemic has meant that she is seeing patients with more advanced cataracts than in the past.

Hill recounted performing a successful operation on a patient who had waited 18 months for surgery as a result of the pandemic.

“I said ‘it is a very dense cataract. Technically it is very difficult and there is higher risk of a problem, but I will do my best.’ He said ‘Love, I can just about see my fingers in front of my eyeball. Whatever you do is better than this’.”

Advertisement

Comments (0)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in