- OT

- Professional support

- Health services

- The new renaissance

The cover story

The new renaissance

A year after the first UK lockdown how can eye care rebuild? From telemedicine in Wales to a drive-through glaucoma service, OT finds out how leaders within the profession are charting a path forward

27 April 2021

In a car park on the outskirts of Guildford, a driver can pull up in the rain, sunshine or snow and ferry a paper bag home on the passenger seat.

This is not a fried chicken craving or quick burger fix, but one of the many ways that eye care professionals have responded to provide care for their patients in the face of challenges posed by a global pandemic.

Since January, more than 400 patients have been seen each week through Royal Surrey NHS Foundation Trust’s drive through glaucoma service.

Patients drive through a designated one-way lane, have their eye pressure checked through the car window and are able to get their eye drops changed if needed in a portacabin.

Glaucoma consultant, Dan Lindfield, told OT that the whole process takes less than five minutes for some patients.

“Even though hospitals are meticulously cleaned and safe, some patients don’t feel confident stepping through the door,” Lindfield explained.

“To be in their own car with their family and just have a hand coming through the window, keeps patients within their comfort zone,” he said.

Establishing a drive through service for glaucoma patients seemed like a “natural step” after similar services were set up for pharmacy, cardiac and maternity patients, Lindfield highlighted.

He added that glaucoma is a potentially blinding disease which is often symptomless.

“Eye pressure is the risk factor but patients have no awareness of it like with blood pressure. There are lots of elements of the testing that we can’t do through the drive through, but we can check eye pressure through a car window. This allows us to measure this key risk factor and keep our patients safe,” Lindfield said.

He added that the service has identified five patients with “dangerously high” eye pressure – all of whom were unaware of their potentially sight-threatening condition.

“This alone makes it all worthwhile. These patents would not have been found if we ran a purely telephone outpatient service or if their appointments were further delayed,” Lindfield emphasised.

Although Lindfield does not envisage a drive through glaucoma service outlasting the pandemic, he highlighted that the hospital eye service needs to work more efficiently to deal with a backlog of patients that has built up during national lockdowns.

Patients seem to be happy to go to the post office to post a parcel or to the shop and buy some milk but they don’t want to come through the hospital door

The glaucoma service currently has a virtual clinic reducing the number of clinicians seen by a patient and speeding up the process. Allied health professionals are involved in the care of patients alongside consultants.

“We are definitely moving away from the traditional model of seeing a doctor after your tests, which is inefficient,” Lindfield shared.

He added that there are further opportunities to refine the patient pathway.

“To have a clinic that just does glaucoma in high volume and efficiently before feeding that data into a senior decision maker would allow the clinician to see more patients. It is just securing the investment, having the bravery to do it and implementing the IT systems,” Lindfield said.

A formidable backlog

Provisional data from NHS England shows that in December 2020 there were 23,000 patients who had been waiting more than a year for ophthalmology treatment. In the same month the year before, only 40 patients had been waiting for that length of time.

Lindfield believes that a key hurdle to overcome in addressing the backlog is making sure that patients feel safe to return to the hospital.

“Patients seem to be happy to go to the post office to post a parcel or to the shop to buy some milk, but they don’t want to come through the hospital door. They see it as a COVID-19 hotspot – which is not true. It is trying to dispel that myth,” he emphasised.

Another issue to address in a post-pandemic health service is that of crowded waiting rooms, Lindfield added.

“Eye clinics nationwide and probably worldwide are guilty of having patients wait two or three hours sometimes for their appointments. That has got to change. It really has to stop,” he said.

CUES: fit for the future?

The task of clearing out hospital waiting rooms could be aided by treating more patients within community optometry practices.

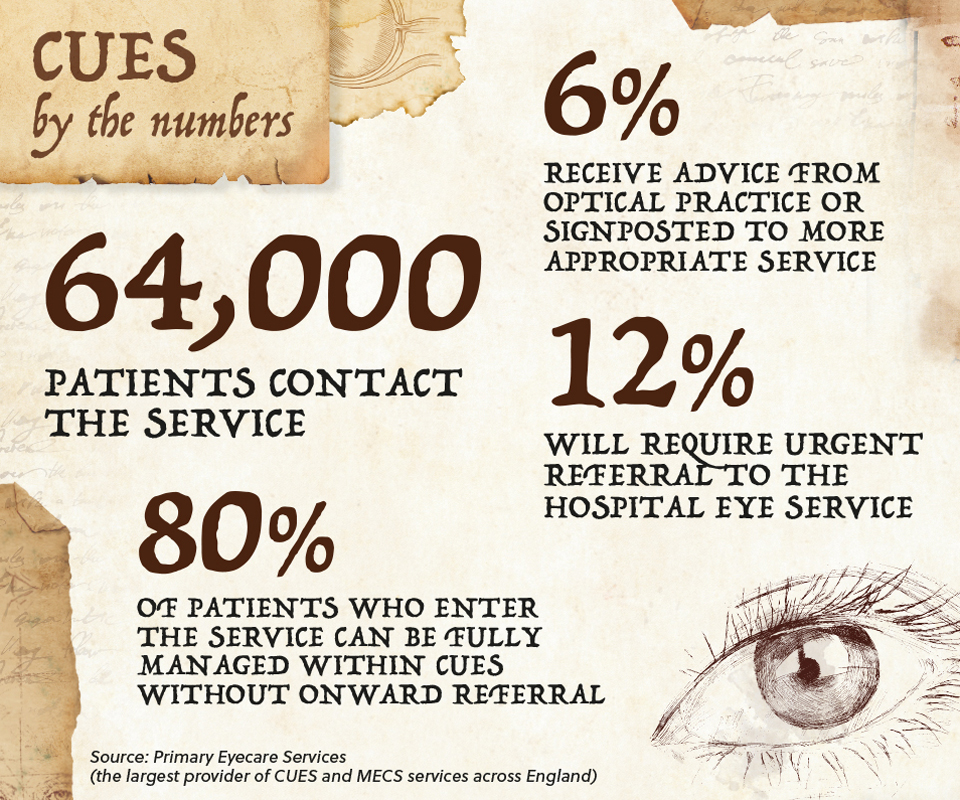

Data from Primary Eyecare Services shows that since the establishment of the COVID-19 Urgent Eyecare Service (CUES) in April last year, more than 64,000 patients have contacted the service in England. Within this group, 6% were redirected through telephone triage to a more appropriate service or received advice on how to self-manage their condition.

Of the patients receiving treatment through the service, more than 80% were managed within primary care optometry with only 12% of patients requiring urgent referral to a hospital eye service.

Primary Eyecare Services is the largest provider of CUES and minor eye conditions services (MECS) across England.

“If we can manage more people in primary care and fewer people need to be seen in the hospital then that is going to benefit the recovery of health services and help with the backlog. There are huge pools of experience in primary care as well as equipment. This is a chance to deliver care differently,” Richmond said.

Across England, 76% of the population now has access to urgent eye care through an optometry practice – either through CUES or through MECS

There are huge pools of experience in primary care as well as equipment. This is a chance to deliver care differently

As well as the convenience to patients of receiving care in their neighbourhood rather than in hospital, Richmond highlighted the benefits for practitioners of CUES and MECS.

“For practice staff, they are able to fully use the scope of the skills that they have – not just in terms of core competency but also the skills that optometrists have gained through additional qualifications,” Richmond said.

A priority moving forward is to make sure that independent prescribing optometrists are able to practise to the full extent of their ability, she added.

“CUES recognises the skills of optometrists with independent prescribing, but it hasn’t necessarily been all that easy to get them the FP10 pads. Although they have the skillset, a number of IP optometrists are having to send their patient through to the GP to get access to prescription medication. That is an unnecessary step to the pathway,” Richmond highlighted.

A year after CUES was first introduced, the environment in which clinicians are operating is shifting. Richmond noted that services are being evaluated at a local level to check what is working and what might work in the future.

“We made some ambitious changes as a response to COVID-19 but on reflection, this care pathway is fit for the future. From my point of view, this is a long-term solution to delivering urgent eye care to people in the local area,” she said.

Richmond emphasised the need for NHS England to work with optometrists to ensure that people have equal access to eye care.

“I think as a professional group we have demonstrated that we can be incredibly agile and responsive at a time of crisis. We could do so much more to help. There are pockets of excellence across England but we need some way of ramping it up so that every practitioner has the same opportunity to meet the needs of their patients,” she said.

The view from practice

Alongside working as an optometrist at Specsavers practices in Chesterfield and Matlock, Alex Howard is a clinical governance and performance lead for Primary Eyecare Services.

Howard, who helped to design and coordinate the roll out of CUES in Derbyshire, highlighted that being involved in CUES gave him a sense of purpose during the initial stage of the pandemic.

“It is about having the chance to contribute in some way during a time when our services were most valuable to people,” Howard said.

He has seen a significant increase in the number of practices that are involved in CUES or MECS in Derbyshire over the course of the pandemic.

Being involved in the service gives practitioners variety within their working day, Howard noted.

“There is a feeling that everyone is working together towards something bigger,” he said.

Howard noted that CUES gives patients an option for accessing eye care locally at a time when many patients have reservations about attending hospital appointments.

He shares the example of a patient who was seen through CUES after developing flashers and floaters just before Christmas.

There is a feeling that everyone is working together towards something bigger

After an examination revealed a retinal detachment, he was urgently referred to hospital for treatment. The same patient developed new symptoms and was referred to hospital again through the service in February with a retinal tear in the other eye.

“In that case, we had a gentleman who, without any intervention, would have permanently lost vision in both eyes,” Howard shared.

Turning to the future of urgent eye care, Howard would like to see equal access to care.

“Different patients receiving different care depending on their postcode is really simply not fair. I think more services should be comparable between areas. There should never be gaps in provision,” he said.

Howard also believes that practitioners should be trusted within the service specification to make decisions about what degree of care is best for their patient. For example, telemedicine is a core element of CUES at present.

“It doesn’t necessarily need to be mandatory in my mind. Some cases are dealt with really well through telemedicine and it definitely has its value, but there are other occasions where you know that the patient just needs to be seen face-to-face. I think the practitioner should have the autonomy to decide over that,” he highlighted.

From office to ocular hub

Following the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns, a shift to home working saw office blocks empty as staff shifted to home working.

On the back of this trend, Moorfields Eye Hospital has trialled using commercial office space to offer care to more patients.

The eye hospital network has opened a series of diagnostic hubs – including within former office space in Hoxton, London.

Patients take a series of tests within a 45-minute visit which are reviewed virtually by a consultant.

They then receive a letter informing them of the outcome of tests and are offered a video or telephone appointment to discuss particular results. Patients are only asked to attend a hospital appointment if the consultant sees something that requires urgent or personal attention.

Moorfields Eye Hospital divisional director and deputy medical director, Dilani Siriwardena, highlighted that expanding the use of diagnostic hubs helped to provide care to more patients.

“We hope that the diagnostic hubs format can be applied in other settings to meet the needs of patients in the safest, most efficient way possible,” she said.

Welsh optometrists embrace telemedicine

In Wales, telemedicine is one tool that optometrists are using in the wake of the pandemic to enhance access to eye care.

More than 300 practices accredited to the Eye Health Examination Wales Service have been supplied with a USB webcam and two USB headsets as part of efforts to bolster the NHS Wales Video Consulting Service.

Virtual consultation platform Attend Anywhere was offered to all optometry practices across Wales from the end of 2020, with more than 100 practices signing up to the platform by the end of February.

Clinical co-lead of the Eye Health Examination Wales Service, Sharon Beatty, shared that feedback on the initiative had been “very positive.”

“It is an opportunity for practitioners to offer healthcare services in a safe and secure way via a video appointment, rather than seeing patients in person. This has benefits for patients, especially those who are unwell, self-isolating, are in full-time work or who have mobility or transport challenges,” she said.

Return to sender: improving referrals

Professor Bruce Evans talks with OT about research examining referrals from optical practices to secondary care

Referrals from community optometry to secondary care are a key part of the puzzle when it comes to transforming eye care in the recovery phase of the pandemic.

A study funded by the AOP and the Central Local Optical Committee Fund has investigated the appropriateness of referrals to secondary care and the proportion of referrals that receive a response.

Professor Bruce Evans, who led the study, told OT that an audit of 905 hospital referrals from optometry practices in Scotland and England found that more than 90% of referrals were necessary.

“We did not find over-referral to be a major problem,” he said.

In both England and Scotland, Evans and his research team found that some optometry practices routinely received replies from the hospital eye service following a referral while other practices received responses infrequently.

Evans noted that while the study revealed some variation in the appropriateness and accuracy of referrals, the main problem they identified was the lack of a two-way flow of information.

“The absence of referral replies means the optometrist does not know whether the patient has been seen in the hospital eye service or what was found, and, in some circumstances, is obligated to re-refer. This may mean a wasted NHS appointment and additional anxiety for the patient,” Evans said.

He added that good-quality replies are important not only for clinical care and to prevent unnecessary re-referrals, but also to serve as feedback that improves the standard and appropriateness of referrals.

Evans noted that, as a profession, optometrists have become acclimatised to not receiving replies but this needs to change in the context of a pandemic where optometrists are managing patients previously seen within the hospital eye service.

“In the context of this closer integration with the NHS, the paucity of replies to optometric referral letters seems increasingly inappropriate,” he said.

In terms of steps that optometrists working in practice can take to make their referrals more effective, Evans recommends including a request for a reply to the referring optometrist within the referral letter.

If a reply is not received and it would be useful for future clinical care, the optometrist can write to the clinic where the patient was seen asking for a report.

The next step would be to approach the hospital eye service clinical lead.

Evans noted that online platforms are increasingly being used for referrals.

“I would suggest that, as a profession, we should only agree to adopt such systems if replies, and/or access to summary hospital eye service information, are built into the system,” he said.

Comments (1)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in

Anonymous28 April 2021

I hope they wind the window down to take the IOP ? I-care presumably. Some HES units will do anything to avoid involving community optometrists in patient care when there is no reason to attend a hospital.

Report Like 269