Our response to the GOC call for evidence on the Opticians Act 1989 and consultation on associated policies

Our submission to the consultation, July 2022

The General Optical Council (GOC) launched its call for evidence on the Opticians Act and consultation on associated policies on 28 March. This could eventually result in some of the most significant changes to regulation for the optical sector in years. The call for evidence ran for 16 weeks, closing to submissions on 18 July.

Below is our response in full, covering eight sections. Throughout this submission, we have predicated our response on maintaining consistently high standards of patient safety and care as well as the definitions contained within the current legislation and guidance.

The AOP is proud to be the leading representative membership organisation for optometrists in the UK, supporting over 82% of practising optometrists on the GOC’s register. Our response has been co-produced through extensive member, sector and stakeholder engagement and communications activity including:

- Member surveys (see below)

- Workshops (AOP Board, Council)

- Committees (AOP Policy Committee, Virtual Policy Group, and Forums)

- Sector body meetings (regular sessions to explore common principles and socialise thinking)

- UK country engagement (joint meetings between the sector bodies and UK country organisations)

- Social media (a range of interactive social media activity including Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn posts)

- Website articles

- Content in Optometry Today

- Press releases from the AOP

As a membership organisation, it is not surprising that member engagement formed a key part of our work on the consultation. As part of this we conducted a survey of registrants. The survey yielded 2,445 responses, the largest number of any that the AOP has conducted in recent times.

We carried out a survey of our members in which we asked about four key areas of the GOC’s consultation:

i. The separation of the refraction and eye examination elements of the sight test

ii. The delegation of elements of the sight test to other professionals such as dispensing opticians

iii. The requirement to verify a contact lens prescription with the original prescriber

iv. The requirement to have a prescription less than two years old before contact lenses are fitted/re-fitted

We have signalled registrants response to these questions throughout the document.

We would like to express our thanks to all those who took part in our sector engagement programme, the insight from which has helped to inform our submission to the GOC.

Contact our Policy team if you have any questions: [email protected]

Section 1: GOC objectives for legislative reform (Para 14-15)

Q5. Are these the right objectives for the GOC for legislative reform?

AOP response: No

The principles set out here are generally sensible and fit in the broad scope of the wider Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) consultation on regulation and opportunities for regulatory reform across health care. However, there are some inconsistencies and issues within the principles of the call for evidence and consultation which need to be addressed before any subsequent work is undertaken. We also think that there are additional points that the GOC should consider in ‘next steps’ planning as set out below.

The GOC has previously indicated that it will consult before any subsequent business case for change to the Opticians Act. We believe the GOC should reaffirm this by explicitly stating that it will conduct a full public consultation before developing a case for change to the DHSC. This should also include a full impact assessment of potential changes, and the costs and benefits of different options. This is essential because of the range, scope and importance of the changes being considered and their potential impacts on public protection and patient safety. Further consultation and assessment of impacts and options should help refine the case for change and make it more targeted, proportionate and effective.

It would also be helpful for the GOC principles to explicitly include reference to working in line with the Professional Standards Authority (PSA) PSA standards of good regulation which are:

- Proportionate

- Consistent

- Targeted

- Transparent

- Accountable

- Agile

Issues to address with the current GOC objectives

The GOC’s introduction to the objectives says that they are non-hierarchical, but objective 1 states that ‘maintaining patient and public safety is the primary objective’. We agree that this is the most important objective, and the AOP’s own response is grounded on its primacy. The GOC should make this clearer.

The objectives should also explain that the burden of proof for any prospective case for the removal of existing legal restrictions should be a robust demonstration that changes to the Act will maintain public protection, and not introduce new risks of harm.

Objective 5 should be reframed to read more simply, for example as ‘ensuring consistency in the whole system of optical regulation, across individual practitioners and optical service providers’.

Objective 7 says that the ‘path of least resistance’ should be taken. This is true when public protection and patient safety can be achieved effectively via different regulatory mechanisms and guidance. However, the GOC should prioritise the most appropriate and proportionate level of regulation required to protect patients and the public from harm. In some cases, this may not be the ‘path of least resistance’, but a safety-focused regulatory model which targets risks of harm and enables a good standard of clinical care from trained and registered clinicians.

Section 2: Protection of title, restricted activities and registers (sections 7, 8A, 9 and 24-30A of the Act)

Q6. What activities should non-registrants be restricted/prevented from doing?

The current restrictions on the activity of non-registrants should remain in place in order to protect the public and patients from harm.

An evaluation of the public’s perceptions shows that sight is the most highly valued sense.1 We can infer that the public would expect that clinical procedures relating to sight should only be carried out by appropriately trained and accountable clinicians. In order to protect the public, it is our view that non registrants should be restricted from undertaking the testing of sight and the fitting of contact lenses.

We also think that the legal restrictions on supply of optical appliances from non-registrants should remain in place, and be more effectively enforced by the GOC, including the supply of optical appliances for those patients classed as ‘vulnerable’ (as defined in the current legislation). We have explained and evidenced this in more detail in our answers to: Section 2, Question 7; and Section 6.

References

- Enoch, J., McDonald, L., Jones, L., Jones, P. R., & Crabb, D. P. Evaluating whether sight is the most valued sense [published online October 3, 2019]. JAMA Ophthalmol

Q7. What activities do you think must be restricted to our registrants?

The current list of legal restrictions on activities that can only be performed by registrants should remain in place in order to protect the public.

It is our opinion that particular patient groups should only be supplied with optical appliances by, or under the supervision of a registered optometrist, or dispensing optician (see answers in Section 6).

This is because the practice of ensuring that the correct appliance is provided can be more difficult because of the patient’s additional needs, for example a patient with dementia, a patient with a learning disability, a patient with a physical disability or a patient with additional sensory impairment. It is also important to note that some patients are more pre-disposed to sight problems. For example, patients with a learning disability are 10 times more likely to have an eye condition than the general population and the proportion is much higher for people with severe or profound learning disabilities. Restricting the supply of optical appliances by, or under the supervision of, a registered optometrist or dispensing optician would provide much needed additional protection to these patient groups as well as increasing the opportunity for early intervention and diagnosis.2

A good example of how these challenges have been addressed is through the roll out of the NHS England Special School Eye Care Service, following a highly successful early adopter programme.

Whilst we think there is value in expanding the list of vulnerable patients in the interests of better clinical care and patient outcomes, it should not be done if and where it risks compromising existing protected groups.

References

2. Learning Disability and Sight loss.pdf (rnib.org.uk)

Q8. What are your views about continuing to restrict/prevent non-registrants from carrying out the following activities?

a) Testing of sight - AOP response: should be restricted

b Fitting of contact lenses - AOP response: should be restricted

c) Selling optical appliances to children under 16 and those registered visually impaired - AOP response: should be restricted

d) Selling zero powered contact lenses - AOP response: should be restricted

Q9. Are there any additional activities that you think should be restricted to registrants?

Based on consultation with members, we have no strong opinion as to the addition of other activities which should be restricted to registrants. However, we do feel that vulnerable patient groups should only be supplied with optical appliances by, or under the supervision of, a registered optometrist or dispensing optician (see also our response to question 6 and 7).

Q10. Is there any evidence that any other post-registration skills, qualifications or training need to be accredited or approved by the GOC (above and beyond the existing contact lens optician and prescribing qualifications)?

AOP response: No

Mechanisms already exist for professional and inter-professional standards in post-registration training to be created and implemented, for example the professional certificate in glaucoma care. The existing post graduate qualifications are delivered by existing education providers such as universities and assured by the College of Optometrists.

We have spoken to several of our members who are education providers who said that the current educational market already enables new provision to be offered where there is demand for it, and that GOC involvement would unnecessarily complicate the delivery landscape.

We do not think there is evidence that GOC accreditation or approval of additional post-registration qualifications or training is necessary. It is unclear from the call for evidence what kind of process the GOC would use to accredit additional qualifications. We are not aware of other healthcare professional regulators, such as the General Medical Council (GMC), undertaking accreditation of additional post-registration qualifications. Were any such accreditation process to be introduced, it would need to be properly resourced, structured and implemented by the GOC, and we think there would be risks of the process not working properly or creating unintended problems.

Standardising the register

The current register lists GOC-approved qualifications (such as Independent Prescribing and contact lens qualifications) and separately lists non-GOC-accredited qualifications such as professional organisation memberships and other training. This is the correct approach, but it would be helpful for the GOC to review how its register is structured and used so that it can be easily searched and understood. It would also be helpful if the GOC considered how the new powers of register annotation could appropriately be used without the need for additional GOC educational accreditation.

There would be a number of benefits for professionals to doing this, including supporting career progression, recruitment and retention. For patients, an easily searchable register will support better signposting at system, place and neighbourhood level within primary care.

Section 3: Regulation of businesses (sections 9 and 28 of the Act)

Q11. Does the basis for extension of business regulation outlined in our 2013 review of business regulation still apply?

AOP response: Yes

We believe that there is a strong case for extending business regulation. This is because in clinical practice the patient’s experience is determined not only by the individual practitioner, but fundamentally by the environment in which they practice, and the demands put on them by their employer. The adequacy of the clinical environment is determined by the business through its policies, processes, and employment practice.

Many businesses also provide pre-registration placements. The clinical environment, supervision, and the ethical standards of a business can make a big difference to an optometrist at the beginning of their career. The new education system arising from the GOC’s education strategic review will put even more onus on employers to provide students with a quality learning environment throughout their education. Our educationalist members note that students are strongly influenced by their placement environments. Businesses should be accountable for the educational environment they provide.

We believe that business registration should be compulsory and should apply to any business entity carrying out protected functions (sight testing, contact lens fitting and dispensing to restricted groups). This would mean extending registration (and therefore regulation) to businesses owned/run by lay owners as well as all registrant-run businesses. It would also include businesses that carry out protected functions but do not employ UK-registered professionals, over which the GOC currently has no regulatory powers.

To enlarge on the above points, our reasons for supporting comprehensive business regulation are:

- All organisations carrying out protected functions and providing services to members of the public should be obliged to meet standards designed to protect patients/customers. This should include online businesses dispensing contact lenses or spectacles to restricted groups, as well as traditional optical practices

- The policies and practices in businesses create the environment for individual clinicians to succeed or fail. This environment includes the physical space, the equipment, management of the appointment diary, the way time is allocated for record-keeping or training and development, referral arrangement (both internal within the practice and to secondary care), and even pay incentives. All these can contribute to better or worse patient care, experience and outcomes. Individual registrants need to take responsibility for their standards of care, but we strongly believe that businesses should be held to account for their part in creating the care environment, and the practice of non-registrants they employ

- Requiring registration would make it easier for the GOC to investigate and prosecute concerns about any aspect of business standards, such as unsupervised dispensing to children or selling appliances without appropriate verification of an in-date prescription, and would enable the GOC to respond to any future changes in business models that might come about as a result of technology changes.

Q12. Are there any advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of extending business regulation in addition to those identified in our 2013 review of business regulation? (Impacts can include financial and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

AOP response: Yes

Our view is that the biggest potential disadvantage of compulsory business regulation could be the creation of an unfair and disproportionate financial burden on smaller businesses which are run by registrants. For a registrant practice owner to pay both individual and business registration from a single practice income would clearly be more burdensome than for a non-registrant owner of a larger business. The GOC would need to consider how to avoid this burden. A few possible ways of achieving this could be:

- To make the business registration fee proportionate to practice income, so that larger businesses pay a larger fee

- To charge a nominal business registration fee but impose more significant penalties for breaches of business standards that are proportionate to the actual harm and business size

- To have different fees for the registrant vs non-registrant owned businesses, that take into account that registrant business owners have already paid an individual registration fee

There are some clear advantages (some already mentioned above) but in summary they are:

- Equal application of standards across all organisations carrying out restricted functions

- Businesses will be required to take responsibility for creating an environment in which excellent care can take place

- The GOC will be able to respond more quickly and flexibly to changes in business practices and set-ups, including online optical businesses

Q13. Do you think the GOC could more effectively regulate businesses if it had powers of inspection?

AOP response: Not sure / no opinion

We recognise how giving the GOC inspection powers could allow the GOC to assure itself that businesses are meeting its standards. However, we believe the use of inspection powers would place burdens on the sector that are likely to be disproportionate to the risks posed to the public and patients.

In fact, a burdensome inspection regime could impair the ability of practices to deliver care services. The effectiveness of inspection regimes has been called into question several times in recent years when organisations which passed inspections were nonetheless found to be operating unsafely. Mid Staffordshire NHS hospital trust is the most notable example of this. A recent study published in the BMJ mapped the problems of NHS providers facing multiple and disparate regulatory and inspection regimes, and concluded that the overall impact actually hindered quality and safety initiatives.3 To be effective and avoid unintended detrimental impacts any inspection process would need to:

- Have clearly targeted and risk-based regulatory goals4

- Be proportionate to the levels of risks in optical practice

- Be accountable and transparent in its design and delivery to ensure it is a trusted process

- Avoid unnecessary overlap with NHS regulatory regimes

- Be responsive to feedback from stakeholders to continuously improve design and delivery of the inspection process

- Be agile to new areas of risk in optical practice

We are pessimistic about the possibility of all the above criteria being met. For example, the risks in optical practice are very low, and any inspection regime would need to be very low-cost and light-touch in order to be proportionate to those risks. To run a comprehensive inspection regime would come at significant cost, which would be passed on to registrants. If the GOC did receive inspection powers, it should be required to account for the way registrants’ money is used and to demonstrate that the burden is justified in the light of the risk involved and the benefit to patients and the public.

It is also unlikely that a regime would avoid overlap with other regimes. There is already an assurance framework for many elements of good business practice for those optical businesses that deliver GOS (which is around 95% of practices). These practices are already obliged to demonstrate compliance with the NHS General Ophthalmic Services contractual requirements, which means that they must already show that they have good employment and clinical governance policies and procedures in place. Optical practices, which are generally small organisations, should not be required to participate in duplicate assurance processes. Preparation for a further inspection assessing the same factors would have a disproportionate impact on their ability to operate.

Although we are sceptical about the GOC having inspection powers, we do believe that the GOC should have the power to investigate complaints about specific examples of failure to meet standards. These would be matters brought to the GOC’s attention by concerned members of the public, whistle-blowers or NHS advisers.

References

3. Oikonomou, E., Carthey, J., Macrae, C., & Vincent, C. (2019). Patient safety regulation in the NHS: mapping the regulatory landscape of healthcare. BMJ open, 9(7), e028663

4. Beaussier, A. L., Demeritt, D., Griffiths, A., & Rothstein, H. (2016). Accounting for failure: risk-based regulation and the problems of ensuring healthcare quality in the NHS. Health, risk & society, 18(3-4), 205-224

Q14. Is there an alternative model of business regulation that we should consider?

Answer: Not sure / no opinion - Whilst there are examples of optometrists in large practices taking on a supervisory role with confidence, we believe that the “responsible optometrist” concept could deflect responsibility for quality from the business owners – who set the organisational policies, procedures and culture. This could mean that individual registrants become scapegoats for problems caused by matters beyond their control. At this point in time, we are not clear what alternative model of business regulation would be appropriate for the profession.

Section 4: Testing of sight (sections 24 and 26 of the Act)

Q15. Should dispensing opticians be able to undertake refraction for the purposes of the sight test? (NB This would be possible only if the GOC were to amend or remove its 2013 statement on refraction.)

AOP response: No

Based on our legal advice, provided by Queen’s Counsel, the Opticians Act does not permit delegation of the sight test. The simple removal of the current GOC statement on the subject would not alter the unambiguous legal position created by the Act. Allowing dispensing opticians to refract, in particular without supervision, would create a significant risk of missed pathology which could endanger the nation’s eye health.

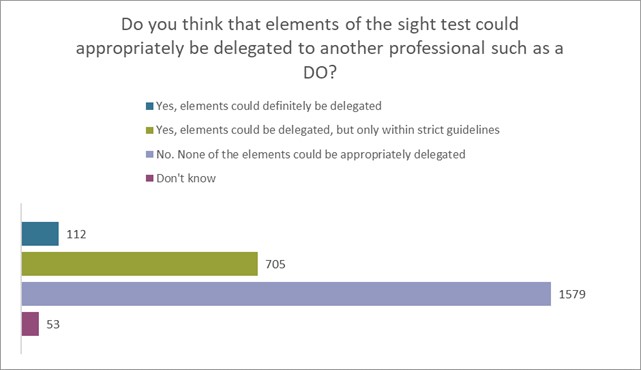

The response to our member survey on the call for evidence indicates that the overwhelming majority of optometrist registrants do not see any significant benefit to patients or practices, should this be allowed. In the survey, we asked, “do you think that elements of the sight test could appropriately be delegated to another professional such as a DO?” We had 2449 responses to this question of which 4.6% said that they ‘definitely’ could, with a further 28.9% saying that they could, but ‘only within strict guidelines’. However, 64.41% felt that ‘no elements’ of the sight test could be safely delegated (see figure 1 below).

Figure 1

Refraction within the sight test goes beyond the simple identification of the patient’s need for visual correction. It is also integral to the overall eye health assessment. During our consultation, members provided us with many examples of where a subtle change in refraction in conjunction with clinical experience alerted them to something that ‘didn’t feel right’ and turned out to be asymptomatic disease. Concerns were also raised that separating refraction from the sight test would weaken the ability to detect general health conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, through characteristic changes to the refractive status.

If we consider a scenario where dispensing opticians were able to perform refraction under the oversight of an optometrist or registered medical practitioner, that would serve to partially mitigate the risk of missed pathology. However, this could produce an unintended consequence in the form of increased pressure on optometrists who are in the role of providing this oversight. Our members, who are GOC registrants, have expressed concern that they may be provided with shorter appointment times that are insufficient to robustly check the refraction. This could increase workplace pressures and lead to clinical errors. These registrants have told us that the clinical governance, audit, and risk measures would need to be sufficiently robust to always ensure patient safety. Clarity of roles and responsibilities was also identified as a key requirement and was felt to be particularly important for locum practitioners.

If the GOC reaches the conclusion that the current statement needs to be withdrawn and replaced with an updated version, it is our view that this should make clear the following points:

- The optometrist, or registered medical practitioner remains responsible for the sight test as defined by the Opticians Act

- An optometrist, or registered medical practitioner may at their discretion be supported by other staff members in the testing of sight, but the decision around what support is provided must remain with the person conducting the sight test

Q16. What would be the advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of amending or removing our 2013 statement on refraction so that dispensing opticians can refract for the purposes of the sight test? (Impacts can include financial impacts and equality, diversity and inclusion impacts.)

Advantages – none. There is a large and well-trained optometry workforce with sufficient capacity to provide high quality eye care to the population. The limited additional capacity that would be provided by dispensing opticians being able to refract would serve no practical purpose and deliver no obvious benefit to patients.

Disadvantages – the removal of the statement would bring the implied GOC position into open opposition to the Act. The Opticians Act does not refer to ‘refraction’. Indeed, the definition of a sight test given in the Act is what is described as refraction in the GOC’s consultation. The Act mandates requirements additional to refraction to ensure that the appropriate eye health examinations are conducted at the same time as the refraction. In our opinion this fact, in conjunction with the misunderstanding that refraction is not central to the definition of the sight test under the Act, is why the suggestion that refraction could be separated from the sight test is flawed.

As refraction is the central element of the sight test, allowing DOs to refract is a clear breach of the Act and, given that DOs are not able to complete the required additional aspects of the sight test, this would risk both patient safety and the integrity of the sight test.

The removal of the statement on refraction could also be perceived as being more permissive than intended with regard to what is allowed within the confines of the Act. This may have the unintended consequence of encouraging businesses further to erode the public protections enshrined within the Act. Our view is that any move of this kind is unlikely to successfully limit refraction to dispensing opticians only, and moreover may have another unintended consequence of enabling some businesses to start to use other healthcare professionals who may not be adequately trained to provide refraction as part of the sight test. This may introduce unnecessary risk.

Q17. Does the sight testing legislation create any unnecessary regulatory barriers (not including refraction by dispensing opticians)?

AOP response: No

The current legislation does not provide unnecessary regulatory barriers. Instead, it establishes a framework to ensure that when sight is tested, the eye health of the patient is also evaluated. This provides an opportunity for the detection of asymptomatic eye disease that otherwise may not be identified until significant, irreparable damage has already occurred. Given the importance of this role and the potential risk to the public, the profile/type of clinician who is able to conduct sight tests is quite reasonably restricted, to ensure that those testing sight are suitably qualified and trained.

Any changes that seek to break the concurrent delivery of these two aspects of eye care risks an increase in the prevalence of undiagnosed eye disease and late presentation of certain eye conditions. For example, it is recognised that around 50% of glaucoma5 6 is currently undiagnosed. There is a significant risk that patients may not appreciate that a refraction alone will not provide the same assurance as the current sight test. Feedback from our members highlights that many patients confuse various appointments already and anything that further complicates that process could lead to missed pathology. Further there is a long-established tradition of UK patients receiving eye health and refractive elements together. If they are separated, patients may believe that both parts have been completed, increasing the risk that patients do not seek to obtain the eye health component.

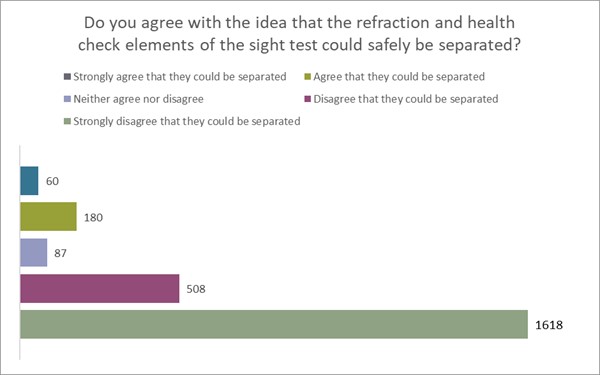

We surveyed our members for their views on this element of the GOC’s call for evidence and received 2452 to this question. We asked, “do you agree with the idea that the refraction and health check elements of the sight test could safely be separated?” Nearly 10% of our members agreed that they could, but 87% disagreed, 66% strongly so. In free text responses on our community forums, members pointed out that such a separation presents a real risk of widening the health inequalities gap caused by socio-economic factors (see figure 2 below).

Figure 2

Some other parts of Europe operate a system of split eye health and refraction, or a reduced eye health function. One such example is the Italian optometric system which is predominantly based around refraction with no obligation to detect ocular pathology. A study by Cheloni7 et al reported that in Italy there were several conditions that would likely remain undetected in this type of eye care model. The authors indicated that around 20% of patients may have ocular pathology that required treatment or monitoring and that would be undetected without the requirement for concurrent refraction and eye health examination.

Langis and Forcier8 reviewed data from a large eyecare centre in Canada and retrospectively reviewed records selecting those presenting only with refractive symptoms and then examined whether on further investigation during the eye examination any ocular diagnoses were revealed. They reported that in 26% of patients, asymptomatic disease was found and although the results were numerically different, they were thematically similar.

A larger-scale study of over 6000 eye care records in Canada (Irving et al9) examined the outcome of asymptomatic patients presenting for what they considered to be a routine eye examination and found that around 58% of patients had a change in ocular status or eye care requirements, suggesting that patients are not well placed to judge when there has been a change to the status of their vision or eye health.

If evidence from the literature were extrapolated to the number of sight tests in England it would mean that approximately 11.6m patients would be unlikely to recognise when a change in their prescription requirements or ocular health necessitated re-examination. Based on the work by Cheloni et al, 4 million patients may have pathology that is not monitored assessed or detected if the two components of the sight test are separated. The lost opportunity to detect asymptomatic eye disease could have catastrophic effects on the nation’s eye health. An additional risk is that patients may continue to drive with substandard visual acuity, reduced visual fields, or reduced contrast vision due to the presence of macular degeneration, glaucoma, or cataract.

In an older population it has been shown that outdated, inaccurate, or inappropriate spectacles may contribute to falls10. Also given the high prevalence of cataract in older population groups, and the gradual and often asymptomatic onset of this condition, the separation of eye health from refractive correction could mean a significant number of people living with undiagnosed cataract and consequently an impact upon contrast sensitivity, ability to detect edges (such as stairs) and a consequent increased falls risk. For information, NHS England conducts around 400,000 cataract operations per year, and the vast majority of these will be diagnosed at sight tests.

References

5. Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma in Australia. the blue Mountains eye study. Ophthalmology 1996;103:1661–9

6. Dielemans I, Vingerling JR, Wolfs RC, et al. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in a population-based study in the Netherlands. The Rotterdam study. Ophthalmology 1994;101:1851–5

7. Cheloni, Riccardo, et al. "Referral in a routine Italian optometric examination: towards an evidence-based model." Scandinavian Journal of Optometry and Visual Science 14.1 (2021): 1-11

8. Michaud, Langis, and Pierre Forcier. "Prevalence of asymptomatic ocular conditions in subjects with refractive-based symptoms." Journal of optometry 7.3 (2014): 153-160

9. Irving, Elizabeth L., et al. "Value of routine eye examinations in asymptomatic patients." Optometry and Vision Science 93.7 (2016): 660-666

10, Lord, Stephen R. "Visual risk factors for falls in older people." Age and ageing 35.suppl_2 (2006): ii42-ii45

Q18. What would be the advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of sight testing legislation remaining as it is currently? (Impacts can include financial and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

Advantages of retaining current sight testing legislation

Maintaining the link between eye health and the testing of sight (refraction) ensures that patients obtaining refractive correction are provided with reassurance that their eye health is satisfactory. This not only ensures that asymptomatic ocular disease is not present, but patients do not labour under the misconception that they aren’t seeing well simply due to the need for different spectacles, when in fact it is undiagnosed eye disease.

Restricting the testing of sight to the currently defined categories ensures that those who test sight have robust training before being permitted to examine patients.

It ensures that the current English system of nationally funded sight tests for those on means-tested benefits is maintained and that the integrity of the examination is not called into question.

Although much maligned, the national sight test fee ensures that patients have access to affordable eye care. Separation would be likely to increase the cost of the eye health portion as patients would attend less often.

The impact on patients of keeping sight testing legislation as it currently stands is obvious: it helps to protect sight; it reduces the risk of increased avoidable sight loss by ensuring a qualified, appropriately trained clinician is responsible for all elements of the patient’s care. This ultimately helps the NHS to be financially and operationally optimal and efficient. It will also help provide some consistency and continuity to the commissioning and delivery of primary eye care services at both ‘system’ Integrated Care System (ICS) and ‘place’ Integrated Care Board (ICB) level and provide confidence to secondary care ophthalmology in the clinical ability of the profession to take on more enhanced services and procedures.

Disadvantages of retaining current sight testing legislation

We do not recognise any disadvantages to the sight testing legislation remaining as it is, as in our members’ view the current legislation is successful in serving to protect patients. However, we do feel that there could be a small risk that the legislation and/or associated guidance as it stands could restrict innovation and the ability to be flexible and reactive to change at the pace required to keep the profession agile within a complex and fast-paced primary eye care system. In our view this risk is not relevant as technological advancements that are used by the optometrist are already permitted, therefore the Act does not prevent their use.

Q19. Do you have any data on the number/percentage of referrals that are made to secondary care following a sight test / eye examination?

AOP response: Yes

According to historic referral surveys11 around 5% of patients who present for a sight test are referred onwards. Based on the current volume of sight tests conducted in England alone, that equates to around 1m patients who are referred for further investigation in relation to suspect pathological eye conditions.

We have been provided with data by one large group of practices in England who conduct a statistically significant volume of examinations. This data corroborates the historic 5% figure, showing that in just over 6% of cases there was a need for the optometrist to refer the patient or write to the patient’s GP as a result of their examination. Extrapolated to the number of sight tests in England alone, this indicates around 1.2 million patients, which is a slight uplift from the historic estimate that reflects the increased diagnostic capability in optometric practice. Of those patients where referral or information to the GP was required it was for the following reasons:

- Cataract, circa 23%

- Glaucoma, circa 14%

- Anterior eye conditions, circa 10%

- Wet AMD, circa 7%

- Neurological concerns, circa 6%

Again, extrapolating this data for England gives:

- Cataract, circa 280,000 patients

- Glaucoma, circa 170,000 patients

- Anterior eye conditions, circa 120,000 patients

- Wet AMD, circa 84,000 patients

- Neurological concerns, circa 72,000 patients

References

11. Port, M. J. A. "Referrals and notifications by optometrists within the UK: 1988 survey." Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 9.1 (1989): 31-35

Q20. Are you aware of any data to support or refute the case for separating the refraction from the eye health check?

AOP response: Yes

Soh et al12 conducted a meta-analysis looking at the rate of undiagnosed glaucoma worldwide. They found that adults without annual eye examinations were nine times more likely to have undetected glaucoma and that there was a link between the period between eye examinations and the likelihood for undiagnosed glaucoma to be present. Meanwhile Chua et al13 also found a high prevalence of late glaucoma diagnosis due to the asymptomatic nature of the disease in the early stages.

If refraction and the eye health examination are separated, in our opinion there is an increased risk that patients will not have regular eye health examinations, which could impact the point at which glaucoma is first identified. The associated costs in terms of social care and lost productivity would be significant. RNIB estimate that the indirect costs of associated sight loss in the UK economy are around £6 billion14.

As we have said above, Cheloni et al reported that 20% of patients may have ocular pathology that requires treatment or monitoring and that would be undetected without the requirement for concurrent refraction and eye health examination. If refraction and ocular health examination were to be separated, then around 4m patients would be at risk of eye disease that would previously have been detected.

A robust and detailed comparative analysis of the primary eye care systems in the UK, France and Germany by Thomas et al15 concluded that each system had its own advantages, and all delivered effective services which were capable of high-quality delivery. Whilst this paper does not show that the UK system is unambiguously better than other European countries, it shows that the system already delivers capably and effectively. Thomas et al also concluded that France and Germany should consider increasing the participation of dispensing opticians and optometrists to deal with upcoming challenges, suggesting that the UK has the most sustainable eye care model.

In our opinion, changing the sight test regulatory framework to separate refraction and the eye health check would be a destabilising, risky and costly process, which would jeopardise a system which evidence shows is already working well.

References

12. Soh, Zhi, et al. "The global extent of undetected glaucoma in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Ophthalmology 128.10 (2021): 1393-1404

13. Chua, Jacqueline, et al. "Prevalence, risk factors, and visual features of undiagnosed glaucoma: the Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases Study." JAMA ophthalmology 133.8 (2015): 938-946

14. The economic impact of blindness and sight loss in the UK Adult population RNIB/Deloittes 2013Report (rnib.org.uk)

15. Thomas, D., Weegen, L., Walendzik, A., Wasem, J., & Jahn, R. (2011). Comparative analysis of delivery of primary eye care in three European countries (No. 189). IBES Diskussionsbeitrag

Section 5: Fitting of contact lenses (section 25 of the Act)

Q21. Does the fitting of contact lenses legislation create any unnecessary regulatory barriers?

AOP response: No

To ensure patient safety, it is both clinically appropriate and necessary that contact lens fitting can only be legally carried out by registered optometrists or dispensing opticians with a contact lens specialty. Contact lenses are medical devices which carry numerous risks of harm16 including infection, corneal damage and sight loss. Initial fitting, refits and rechecks with registered optical professionals are vital to ensure that patients are protected from these risks of harm, as we have explained in our answers to questions 22 and in Section 2 and Section 6. The UK has an accessible network of optical practices which are able to offer fittings and follow-on care to patients who want to wear contact lenses.

References

16. Wolffsohn, J. S., Dumbleton, K., Huntjens, B., Kandel, H., Koh, S., Kunnen, C. M., ... & Stapleton, F. (2021). BCLA CLEAR-Evidence-based contact lens practice. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 44(2), 368-397

Q22. What would be the advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of fitting of contact lenses legislation remaining as it is currently? (Impacts can include financial impacts and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

Patients should only initiate contact lens wear under clinical supervision during a fitting with a registered optical professional. GOC-registered practitioners fit contact lenses based on a thorough assessment, taking into account clinical measurements, ocular health and the patient’s individual needs and wellbeing. Once the fitting is complete and patients have been taught how to insert, remove, handle, clean and store the lenses safely, practitioners typically arrange a further check to ensure the lenses are suitable before issuing a specification for supply. The requirement for contact lens fitting to be carried out only by registered optometrists or dispensing opticians helps ensure that patients:

- Understand how safely to wear, store and care for their contact lenses

- Understand how to look for signs of infection or other problems

- Know how to obtain optical care if problems occur

It is encouraging to see that the call for evidence does not suggest that the GOC is considering any changes to fitting regulations. However, in order to ensure that patients are protected from harm and continue to use lenses safely after fitting it is also important that restrictions on sale and supply of contact lenses are kept in place, as we have explained in our answers to Section 6. Taken together this package of regulation helps ensure that patients receive ongoing care from optical professionals as they use their lenses. This includes safety advice about lens use, assurance that lenses are supplied to the correct specification, and management of risks associated with disease and infection. Studies of compliance with advice about contact lens use suggest that regular clinician reviews of care help reinforce patient behaviours that promote safe lens wear.17

References

17. Morgan, P. B., Efron, N., Toshida, H., & Nichols, J. J. (2011). An international analysis of contact lens compliance. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 34(5), 223-228

Section 6: Sale and supply of optical appliances (section 27 of the Act)

Q23. Should the sale and supply of optical appliances be further restricted to certain groups of vulnerable patients?

AOP response: Not sure / no opinion

We believe that there is a case to consider adding patients with learning disabilities, older people in residential care and those with complex conditions which increase the likelihood of eye problems to the list of vulnerable groups who need to have optical appliances supplied to them under the supervision of an optometrist, dispensing optician or medical practitioner. It is accepted that vulnerable patient groups may include:

- Those with a dementia disease such as Alzheimer’s

- Adults with a learning disability

- Adults with a complex physical disability

- Older adults in a residential care setting

- Those patients with an existing sight condition such as glaucoma

These groups have a high prevalence of eye disease18, 19 which means that they would benefit from having their optical appliances provided under clinical supervision.

The case for adding these groups would also be strengthened if the GOC is considering the removal of restrictions on the sale and supply of optical appliances which apply to all patients.

However, this should only be done if this has support from patient organisations who represent these vulnerable groups. Practical issues of implementing these restrictions and whether the changes will lead to overall benefit and protections for patients are important considerations.

References

19. Emerson E, Robertson J The estimated prevalence of visual impairment among people with learning disabilities in the UK (2011)

Q24. If you answered yes to the previous question, what would be the advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of further restricting the sale and supply of optical appliances to certain groups of vulnerable patients? (Impacts can include financial and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

The higher prevalence of eye disease in these groups means that many patients will have eye conditions for which it is beneficial to have clinical supervision alongside the supply of optical appliances as well as additional interventions where appropriate:

- A specialist lens or fitting for the optical appliances may be needed

- Contact with a practitioner could help identify changes to the patient's eye condition or corrective needs

- The patient could be referred to another service or given advice to support them with their current clinical, support or visual corrective needs

- The risk of falls in older people could be mitigated by appropriate visual correction intervention

The main disadvantages of adding these groups to the list of vulnerable groups is that many people within these vulnerable groups may not require additional support. This could lead to issues and perceptions of unfairness and barriers to access for them. It may also create an increased cost burden on these groups. Provision of clinical support for people with learning disabilities is likely to work better in areas where targeted eye care and support services have been commissioned, but this varies across the UK.

There would also be practical challenges in how to identify the patients who belong to these vulnerable groups. Registers for people with learning disabilities, living with complex conditions and in residential care do exist, but there is no national register equivalent to that for people with a visual impairment.

Q25. Do the general direction / supervision legislative requirements relating to the sale of prescription contact lenses create any unnecessary regulatory barriers?

AOP response: No

We do not think that the current legislation creates unnecessary regulatory barriers. The current restrictions are in place to ensure that patients have a safe level of clinical assurance that they are being supplied with appropriate lenses and that the patient has had a recent sight test and contact lens fitting. We have explained the risks of these restrictions being relaxed or removed in our answer to question 26, and throughout this section.

Q26. Would there be a risk of harm to patients if the general direction / supervision requirements relating to the sale of prescription contact lenses changed?

AOP response: Yes

The current process provides safeguards to protect patients by ensuring that:

- The lenses being supplied match the specification, and the choice of lens is in the patient’s best interest

- That the specification is accurate and based on a recent contact lens fitting and sight test

Removal or relaxation of these supply restrictions could lead to a risk of patients using contact lenses without regular refits and rechecks with an optical professional, or in some cases having never being fitted for them. Contact lens wear carries various risks of infection and corneal damage.20 As we explained in our answer to Section 5 and throughout this section, without appropriate advice about how to care for, clean, and store their lenses, there is a significant risk that patients develop unsafe contact lens habits. This may increase the risk of developing sight loss-causing infections.21

Acanthamoeba keratitis is a rare but severe corneal infection that affects mainly contact lens wearers in Western countries.22 It can lead to visual impairment and blindness, and it can develop as a result of poor contact lens hygiene and exposure to tap water. This is why regulations that ensure the patient has had a recent contact lens fitting and provision of aftercare are essential. Our answers to the questions about zero-powered lenses further explain why non-legislative approaches are insufficient to ensure public protection.

There are also several risks of harm to patients from being supplied with lenses that do not match their specification, which can result from a failure to verify contact lens particulars or inappropriate contact lens substitution. The problems that can result are set out in our answer to question 28 and these include risks of corneal damage and eye infection, poorer visual fit, acuity and eye discomfort, and a risk of failing to meet vision standards for driving.

Proportionate modification of the requirement

We disagree with the GOC’s reasoning about the contact lenses verification requirement being ‘outdated’, but there may be ways sensibly to update requirements whilst also maintaining safeguards to ensure patients are being appropriately and safely supplied. Current legislation requires that the seller should verify the specification with the prescriber when supplying under general direction (unless the patient is able to supply an original in-date specification).

We think it would be acceptable to relax this requirement by:

- Allowing electronic copies (such as a photo, or scan) of the specification to be provided without the need for verification

- Requiring the seller to verify the specification with the original prescriber if there is any doubt about what the particulars of the specification are, for example if they cannot be read properly or if there is anything to suggest that it may have been tampered with

References

20. Wolffsohn, J. S., Dumbleton, K., Huntjens, B., Kandel, H., Koh, S., Kunnen, C. M., ... & Stapleton, F. (2021). BCLA CLEAR-Evidence-based contact lens practice. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 44(2), 368-397

21. Stapleton, F., Keay, L., Jalbert, I., & Cole, N. (2007). The epidemiology of contact lens related infiltrates. Optometry and vision science, 84(4), 257-272

22. Carnt, N., & Stapleton, F. (2016). Strategies for the prevention of contact lens‐related Acanthamoeba keratitis: a review. Ophthalmic and physiological optics, 36(2), 77-92

Q27. Do the legislative requirements for verification of contact lens specifications create any unnecessary regulatory barriers?

AOP response: No

The requirement to verify a contact lens specification when supply is under general direction, and the original has not been provided, is a safeguard to ensure that patients are supplied with the appropriate lenses without a risk of detrimental impacts. The risks that can result from being supplied with lenses that do not match the specification include corneal damage and eye infection, poorer visual fit, acuity and eye strain, and a risk of failing to meet vision standards for driving. We have provided more detail about these harms in our response to question 28. Verification of the specification also provides assurance that the patient has had a recent contact lens fitting, and better enables the seller to make reasonable aftercare arrangements to protect the patient from risks of harm related to contact lens wear.

A key problem with the current regulatory situation is that sellers implement the existing legislative requirement to verify a contact lens specification in a variety of ways, and some sellers, especially those based online, fail to fulfil the current public protection requirements.

The need to verify the specification should remain in place where there is doubt about the particulars of the specification, although there is scope safely to update the verification requirement to allow acceptance of electronic specifications (as we have set out in our answer to question 28). It is important that any changes to the current requirements are properly enforced by the GOC, and breaches are dealt with through regulatory action based on its illegal practice protocol to ensure consistent application of verification requirements by sellers. We have proposed ways that the GOC can deal with online sellers breaching the Opticians Act, including those based overseas, in our answers to questions 50 and 51 in Section 7.

Q28. What would be the advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of removing the requirement to verify a copy of or the particulars of a contact lens specification? (Impacts can include financial and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

Risks of inappropriate lenses being supplied

The reason this requirement is in place is to ensure that the lenses being supplied by the seller correctly match the patient’s contact lens specification. Removing the requirement to verify the specification when an original has not been provided will increase the probability that patients are supplied with inappropriate lenses not matching their specification. Detrimental consequences for patients can result both from being supplied with an incorrect lens power, but more seriously from poorly fitting lenses that do not match an individual’s eye shape. Resulting patient harms include:

- Lenses that cause mechanical damage to the cornea due to a poor fit, or lead to corneal damage as a result of physical characteristics of the lens, such as how well the surface stays hydrated

- The oxygen transmission of the lens may not be as anticipated by the prescribing practitioner when providing advice on how long it is safe to wear the lenses

- Corneal damage can increase the risk of eye infections including potential sight-threatening diseases such as microbial keratitis

- Contact lenses that fit poorly can reduce visual acuity and lead to discomfort. This is a particular concern with varifocal contact lenses which have more complex prescriptions

- Where a patient only just meets the required visual acuity standard for driving when vision is corrected by contact lenses, a contact lens which does not match their current specification could lead to the patient not meeting the required standard, potentially leading to them driving illegally and risking harm to the patient and other road users

Risks of reduced contact with optical professionals

Removal of the requirement to verify the contact lens specification will mean that patients may be able to purchase lenses simply by providing their spectacle prescription to the seller or, worse, by simply guessing. This would increase the risk that patients delay attending for a contact lens fitting beyond two years. The risk of this happening has increased due to the increased availability of contact lenses online, and a recent study of patients buying contact lenses on the internet found a growing number who initiated lens wear independently without professional care and advice.23 Less frequent contact lens care and advice from optical professionals will increase the risk of patients developing poor contact lens hygiene habits and increasing the risk of developing harmful infections that could lead to sight loss, as we have explained in our answer to question 26. If patients reduce their engagement with optical professionals, there will also be reduced opportunities for emerging risks and signs of infection and corneal damage to be identified.

Problems with drawing lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic

In its call for evidence the GOC says that during the COVID-19 pandemic it relaxed the verification requirement ‘without any detrimental effects that it knows of’. The problem with using this as a basis for changing the verification requirement is that:

- It is still too early to evaluate the impacts of relaxing regulatory restrictions during the pandemic and problems that have resulted from this may still come to light, potential sight loss from delays in diagnosis of eye disease take time to develop

- Contact lens use went down during the pandemic as people were in lockdown24, which may have led to reduced prevalence of problems related to contact lenses

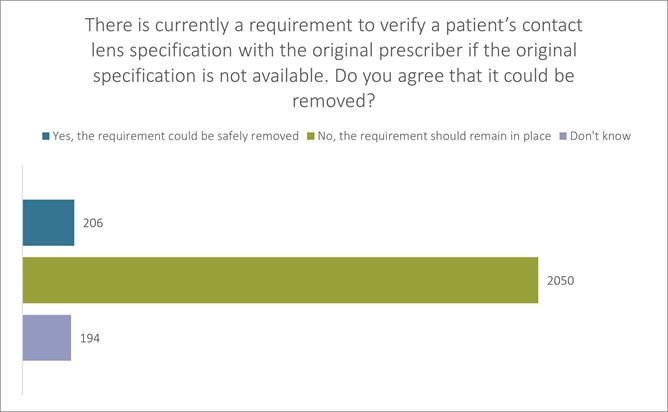

We consulted our members on this question, receiving 2450 responses. We asked, “there is currently a requirement to verify a patient’s contact lens specification with the original prescriber if the original specification is not available (such as when supplying contact lenses online). The GOC is consulting over whether this requirement could safely be removed. Do you agree that it could be removed?”

8% agreed that the requirement could be safely removed, but 84% said that it should remain in place (The remaining 8% said they did not have a view). (see figure 3 below).

Figure 3

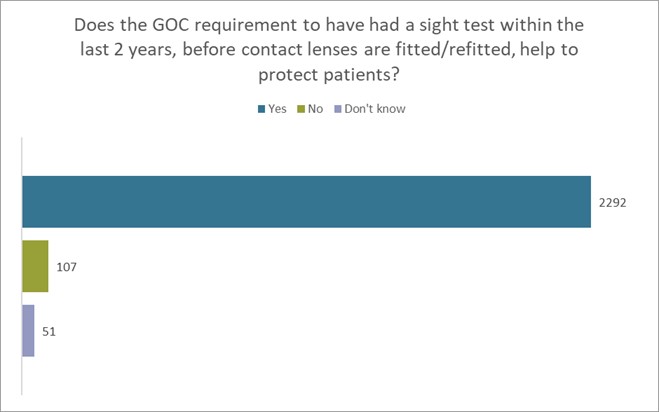

Furthermore, we also consulted our members on the following question, receiving 2450 responses. We asked, “Does the GOC requirement to have a sight test within the last 2 years, before contact lenses are fitted/refitted, help to protect patients?” 94% agreed that the current GOC requirement does help protect patients (see figure 4 below).

Figure 4

Proportionate modification of the requirement

We disagree with the GOC’s reasoning about the contact lenses verification requirement being ‘outdated’, but there may be ways sensibly to update requirements while also maintaining safeguards to ensure patients are being supplied appropriately and safely. Current legislation requires that the seller should verify the specification with the prescriber when supplying under general direction, unless the patient is able to supply an original in-date specification. We think it would be acceptable to relax this requirement by:

- Allowing electronic copies (such as a photo, or scan) of the specification to be provided without the need for verification

- Requiring the seller to verify the specification with the original prescriber if there is any doubt about what the particulars of the specification are, for example if they cannot be read properly or if there is anything to suggest that it may have been tampered with

References

23. Mingo-Botín, D., Zamora, J., Arnalich-Montiel, F., & Muñoz-Negrete, F. J. (2020). Characteristics, behaviors, and awareness of contact lens wearers purchasing lenses over the internet. Eye & Contact Lens, 46(4), 208-213

24. Morgan, P. B. (2020). Contact lens wear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 43(3), 213

Q29. Do you think the Act should specify a definition of aftercare? (If yes please specify what you think the definition of aftercare should be.)

AOP response: Yes

Current situation

Because aftercare is not defined in the Act, optical professionals meet this requirement in different ways – as follow-on care which helps protect patients from the risks of harm associated with contact lens use. Many practitioners refer to a recheck appointment or refitting and reissuing of a contact lens specification at its expiry as being part of aftercare. While this may be true, in our opinion it does not address the aftercare requirement as mandated by the Act. Professional bodies for optometrists provide the following advice about delivering the aftercare requirement:

- Our own advice to AOP members advises that they “give instructions on the use and care of the lenses”, and “Use your clinical judgement to decide when to call your patient back for a contact lens check-up or eye examination”

- College of Optometrists professional guidance on aftercare advises practitioners to make aftercare provision “as far as and for as long as may be reasonable” and that it should include “practical arrangements for aftercare with an appropriate provider”. It goes on to list a range of provisions including: a point of contact for the patient; advice about lens use and patient advice on identifying risk of infection; a contact lens helpline; monitoring aftercare arrangements

- The General Optical Council (Contact Lens (Qualifications etc.) Rules) Order of Council 1988, refers to aftercare and states, “The fitting of contact lenses shall be accompanied by the necessary instruction and information to the person fitted on the care, wearing, treatment, cleaning and maintenance of such lenses and the person fitting such lenses shall be obliged to provide for clinical management and adjustment of the fitting thereof for a period of six months from the date of first fitting.” Modern single use lenses rarely need these adjustments. However, it was clearly the intention that the person fitting lenses should provide aftercare.

Defining aftercare for contact lens suppliers

In the past, the vast majority of patients purchased their supply of contact lenses from the same provider that carried out the contact lens fitting or refit and, in that scenario, the 1988 reference to aftercare would have previously been sufficient to ensure patients received appropriate follow-on care. However, as the online market for contact lenses grows, there has been and is likely to be an increasing separation of fitting from supply. This makes the sellers’ duty of aftercare even more important to protect patients. Providing a definition of aftercare could help to ensure that patients who purchase from online suppliers are given suitable advice on how to safely use their lenses and what to do if they experience problems with them. Our suggested definition for aftercare would be:

‘To ensure that those who sell or supply contact lenses to patients are mandated to ensure follow-on arrangements for care are in place, which provides the patient with a reasonable means to safely use the supplied contact lenses, identify signs of infection or other harm and to obtain suitable care or advice if problems occur. It would seem reasonable to draw inspiration from the 1988 rules, but with the onus on the supplier’.

It is vital that any new definition of aftercare is consulted on by the GOC in order to avoid unintended consequences, ensure that it can be reasonably implemented by suppliers and that it can be consistently applied as a duty on all sellers, including those based solely online.

Q30. Does the zero powered contact lenses legislation create any unnecessary regulatory barriers?

AOP response: No

The requirement for zero-powered lenses to be sold by or under the supervision of a registered professional is necessary and proportionate in order to protect the public from serious risk of harm through eye infection which could lead to sight loss. The risk to eye health from contact lenses is not defined by the power of the lenses, but the way it is worn, handled, and cared for; as such we see no reason that zero-powered lenses should be treated more leniently than power lenses. The UK has a large and accessible network of primary care optometric practices which can fit and supply the public with cosmetic lenses and provide them with advice about safe lens use and storage, and aftercare in order to protect them from these harms.

Q31. Would there be a risk of harm to patients if the requirements relating to the sale of zero powered contact lenses change?

AOP response: Yes

The physiological risk of serious harm resulting from eye infection, including sight loss, can result from the unsafe use and storage of cosmetic lenses in the same way as from prescription lenses for vision correction.25 Without appropriate advice about how to care for, clean and store their lenses there is a significant risk that lets users develop poor habits that could lead to sight-threatening infections. Acanthamoeba keratitis is a rare but devastating corneal infection that affects mainly contact lens wearers in Western countries.26 It can lead to visual impairment and blindness; it can develop as a result of poor contact lens hygiene and exposure of the contact lenses to tap water.

Other forms of microbial keratitis are also associated with poor lens hygiene and can lead serious harmful eye infections, but acanthamoeba carries the highest risk of harmful consequences.27

References

25. Kerr, N. M., & Ormonde, S. (2008). Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with cosmetic contact lens wear. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online), 121(1286)

26. Carnt, N., & Stapleton, F. (2016). Strategies for the prevention of contact lens‐related Acanthamoeba keratitis: a review. Ophthalmic and physiological optics, 36(2), 77-92

27. Carnt, N., Samarawickrama, C., White, A., & Stapleton, F. (2017). The diagnosis and management of contact lens‐related microbial keratitis. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 100(5), 482-493

Q32. If you answered yes to the previous question, is legislation necessary to mitigate this risk?

AOP response: Yes

We believe that the current legislation protects users of zero-powered lenses and is necessary. There would be a significant risk of increased harm to wearers of cosmetic lenses if current restrictions on the sale of zero-powered lenses are relaxed or removed because:

- The removal or relaxation of regulation on the sale of zero-powered lenses could send out the incorrect and dangerous message to the public that there aren’t any risks associated with the use of cosmetic lenses

- A lack of regulation will increase the likelihood of individuals purchasing their lenses without any advice about wearing and caring for their lenses from a professional registrant. Tellingly, a multi-centre study28 in France found that the likelihood of microbial keratitis infection developing in lens wearers was increased by a factor of 12.3 when an eye care profession was not involved in the sale of cosmetic lenses

- New sellers are likely to start marketing and selling cosmetic lenses to users if current sales restrictions are removed:

- Sellers may fail to provide sufficient advice about lens care to protect patients

- Even if sellers understand the risks, they may underplay these to customers, as they wouldn’t need to meet the same standards of care as professional registrants

- Prevalence of harmful eye infection associated with cosmetic lens use is highest amongst young people29, and this group will be harder to reach with advice about safe lens use

- The most significant harm would be to individual lens wearers who suffer sight loss as a result of infection, but an increasing number of infections could also lead to increased pressures for already overstretched hospital eye services and further delays for all patients

Non-legislative approaches to public protection

While legislative restrictions should remain in place for the sale of zero-powered lenses, other approaches should also continue to be used to ensure that cosmetic lens users are protected from harm. Legislative restrictions reduce the risks of harm, but sellers are likely to continue to operate outside the legal framework and zero powered lens users will need additional messages about how to reduce their risks of harm from lens wear.

Public education about the risks of cosmetic lenses is important and can help reduce the risk of harm. The AOP has regularly produced advice and information for patients and professionals about the risks of wearing cosmetic lenses, such as this press release about novelty lenses at Halloween. However, the younger age group who are the most likely to engage in more risky lens use behaviours which lead to harmful infection are also one of the hardest demographics to reach with public health advice. Safe lens use campaigns such as Love your Lenses are helpful at reducing harm and have rightly received support from the GOC, AOP and other bodies. However, these safety messages are most likely to work at reinforcing safety advice for existing lens users who have engaged with eye care services. Some cosmetic lens users may have never previously had a contact lens fitting, or even a sight test or contact with any eye care service.

Contact lens packaging could also carry prominent warnings about the risks of poor contact lens hygiene and usage. This approach has been used effectively in differing ways for cigarette and alcohol packaging. However, this would itself require legislation. It is unlikely that manufacturers would voluntarily add such warnings without being mandated or incentivised to do so.

References

28. 937–944. 14. Sauer A, Bourcier T, French Study Group for Contact Lenses Related Microbial K. Microbial keratitis as a foreseeable complication of cosmetic contact lenses: a prospective study. Acta Ophthalmol 2011; 89: e439–442

29. Gray, T. B., Cursons, R. T., Sherwan, J. F., & Rose, P. R. (1995). Acanthamoeba, bacterial, and fungal contamination of contact lens storage cases. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 79(6), 601-605

Q33. What would be the advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of zero powered contact lenses legislation remaining as it is currently? (Impacts can include financial and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

We believe it is important for public protection that the legislation around zero-powered lenses remains. The advantages of this are:

- The legal requirement about the sale and supply of zero-powered lenses sends out a clear message that they are a regulated medical device and need to be used with appropriate clinical advice and care in the same way as prescription lenses to avoid risk of harm

- Evidence shows that cosmetic lens users are less likely to suffer infections that can lead to severe sight loss if they have appropriate advice from an eye care professional on purchase

- The current restrictions protect young people, as the demographic who are the most likely to be users of cosmetic lenses

The potential disadvantages of retaining the current restrictions centre around challenges in enforcing the current regulations and dealing with the risks associated with online sales:

- The GOC may lack appropriate resources of enforcements to tackle all UK websites and retail outlets selling cosmetic lenses without oversight from an optical professional

- The GOC may find it particularly challenging to mitigate the risks to the public from non-UK sales of cosmetic lenses, as consumers increasingly switch to online purchasing habits – again there is likely to be a disproportionate risk of harm to young people who have not had a contact lens fitting

These disadvantages and resultant eye health risks can be mitigated by the GOC taking a strong public protection approach to its enforcement activity based on its illegal practice protocol. This includes taking action against illegal sales in UK retail outlets (such as fancy-dress shops) and referral to trading standards officers where necessary. The GOC should also develop a better strategy to deal with patient safety risks arising from online sales and from sellers based outside the UK as we have explained in our answers to question 50 and 51. The GOC should consider whether it needs new powers in order to properly achieve this.

Q34. Are there any unnecessary regulatory barriers in the Act that would prevent current or future development in the sale of optical appliances or competition in the market?

AOP response: No

Q35. If you answered yes to the previous question, what would be the risk on the consumer if these barriers were removed?

AOP response: N/A

Q36. Is legislation regarding the sale of optical appliances necessary to protect consumers (except restricted categories)?

AOP response: Yes

It is clear from the substantial evidence of risk30 of harm to patients that can result from sale and supply regulations not being followed that continued GOC enforcement of this legislation is necessary to protect the public. The current restrictions fundamentally help protect the public from two key areas of risk:

- Risks of developing severe eye infection that can lead to sight loss, associated with a failure to engage with eye care professional advice and safely care for contact lenses

- Risks of developing eye disease that is asymptomatic and can lead to sight loss, associated with purchasing optical appliances for vision correction without attending a sight test which can detect the early sign of pathology

The whole package of current sale and supply restrictions works to protect patients from these areas of risks which can lead to severe detrimental consequences of sight loss and disease. As we explain across our answers to this section, there are a small minority of areas which may require some revision, but otherwise legislative restrictions on sale and supply should remain in place and be enforced by the GOC as part of the illegal practice strategy. In fact, the Europe Economics risks assessment, commissioned by the GOC in 201431 to identify the costs of illegal practice, concluded that “misdiagnosis of diseases has both a high severity of an adverse event, and a medium-high likelihood of an adverse event occurring under illegal practice”.

GOC enforcement

Given the risks of harm related to optical appliances, we are concerned by the GOC’s view, expressed in the call for evidence, that it is not practicable for it to pursue prosecutions in the magistrates’ court for breaches of UK law relating to legal restrictions on sale and supply of optical appliances. Prosecution is rightly the final step of enforcement but is necessary when other attempts at encouraging regulatory compliance fail, in order to challenge harmful practice by UK sellers which can lead to patient harm.

We accept that the GOC faces challenges when it comes to encouraging online sellers based overseas to comply with UK legislation. However, the GOC’s recent revisions to its illegal practice protocol include strategies to help address this – such as contacting the online marketplace where optical appliances sales are listed. In order to protect the public from harm the GOC needs to strengthen this approach in the ways we have set in our answer to questions 50 and 51. This includes improving public education about risks, contacting the seller and developing a way that patients can identify which sellers are operating within UK law.

References

30. The evidence of harms is referenced throughout our answers to this section on sale and supply restrictions

31. Europe Economics report: health risk assessment for illegal optical practice (2014), GOC website

Q37. Is the two-year prescription restriction on purchase of spectacles from non-registrants an unnecessary regulatory barrier?

AOP response: No

It is vital that this requirement is kept in place in order to protect patients from the risk of severe harm and sight loss. As we have explained in our answer to question 38, removing it would increase the risk of delayed diagnosis of severe eye disease and other detrimental impacts.

Q38. What would be advantages, disadvantages and impacts (both positive and negative) of patients being able to purchase spectacles from non-registrants without a prescription dated in the previous two years? (Impacts can include financial and equality, diversity and inclusion.)

AOP response: No

The removal of this requirement would increase the likelihood that patients delay getting a sight test beyond the recommended two years, increasing the risks of delayed diagnosis of severe eye disease and using spectacles which are unsuitable for their current vision correction needs. In fact, the risk that patients delay or forgo sight tests have increased over time due to the emerging availability of unregulated online self-refraction services. The risks associated with removing the requirement for an in-date spectacle prescription are likely to exacerbate health inequalities as patients who are less health literate will be most likely to delay sight tests, and severe disease such as glaucoma disproportionately impacts some ethnic groups more than others. It could also delay the detection of systemic conditions through case findings during the sight test, such as cardiovascular disease in groups who are otherwise unlikely to engage with healthcare professionals.

The GOC call for evidence says that ‘some patients are not happy with this requirement [for an in-date prescription]’. However, this is a very weak basis for considering change to regulations that would introduce risks of harm for the whole patient population. It may also suggest that patients are not always aware about the important role the sight test plays in safeguarding their eye heath.

Removing the current requirement for an in-date prescription for spectacle sales could also increase the exposure of patients to mis-selling by non-registrants.

Delayed diagnosis of eye disease