- OT

- Professional support

- Clinical and regulatory

- Great expectations

The cover story

Great expectations

As a new approach to optometry education launches, OT talks with students and lecturers about their aspirations for the future of the profession

09 December 2023

A handwritten recipe for spaghetti bolognese, bright wristbands fading as the week progresses, the lone oven glove left on the pavement by parents balancing tea towels, crockery and their sadness outside university halls.

This milestone marks the culmination of years of work by universities and the General Optical Council (GOC) to ensure that the education and training of optometrists remains fit-for-purpose.

The updated education and training requirements (ETR) will see professional placements incorporated into degree schemes, with the pre-registration year that has been a fixture of optometry training for decades ceasing to exist in its current form for students on a Masters course.

Professor Joy Myint is chair of the Optometry Schools Council (OSC). She was responsible for developing both the first and the revised integrated Master of Optometry courses at the University of Hertfordshire, and is now working on designing the Master of Optometry programme at Cardiff University.

Each programme is an exercise in fitting together a jigsaw of GOC and university requirements, while making sure that every element of the course is relevant to students.

“The students keep me motivated. They are the future of the profession,” she said.

“I am now at the stage in my life where retirement is closer than being newly-qualified. I have my degree, I have my GOC registration and now I am helping others to achieve those milestones. It is their time now,” Myint said.

She believes that the ETR has helped to update an educational framework that had become outdated.

“I agree that something needed to change. We do have a set of learning outcomes that better reflect what optometrists and dispensing opticians need to do in practice,” Myint shared.

However, she emphasised that academics were doing what they could within the previous framework to give students the right mix of skills and knowledge.

“There is nothing wrong with the existing degrees at all,” she said.

“I think it was more that the core competencies and requirements that we had to work towards were quite limited. If institutions had stuck rigidly to only what the GOC required, then I think the optometrist possibly would not have skills that were fit for purpose. However, we have all moved with the times,” Myint explained.

Myint uses teaching students about optical coherence tomography as an example of technology that is already taught by most universities but was not a previous GOC requirement.

“We have introduced new techniques that don’t necessarily fit into a core competency because as educators we want to ensure that we are developing optometrists who are practice-ready,” she said.

The new learning outcomes give educators the flexibility to move with developments in practice and technology, rather than focusing on ensuring that every core competency is evidenced.

“We are able to respond to developments in technology because it is no longer concentrating on specific clinical techniques, it is being able to perform an eye examination that is appropriate to the patient that is in front of you,” Myint explained.

“If artificial intelligence (AI) or other emerging technology comes to the fore, we can ensure that our students are introduced to that at an appropriate time,” she said.

A key aspect of the updated framework is an overhaul of how professional placements are provided. Rather than a two-stage process, where students complete a pre-registration period that is usually separate to their university study, all clinical placements will be integrated into their university programme.

The OSC has been meeting with employers from a range of settings to discuss how these placements might work.

“We need to make sure that we are working together. With the traditional model, it was very easy to do a degree then you go out on placement, and you had nothing to do with the university,” Myint said.

“Now it is all integrated we need to make sure that we are singing from the same hymn sheet – that the employers know when the students go on placement what level they are at, what they can and cannot do,” she shared with OT.

Myint highlighted that the placements will not be as big a change as some people fear.

“Students will go out in practice, they will test under supervision, they will learn from their supervisor. That fundamental experience is still very similar,” she said.

We do have a set of learning outcomes that better reflect what optometrists and dispensing opticians need to do in practice

Asked whether commercial pressures on placements are a concern, Myint observed that there have been instances of this under the previous framework.

“We have raised this with the GOC previously. The big change, for some universities, will be that they will still be our students. As universities we have responsibility for those students, so we need to look out for the signs of commercial pressures. That is why the relationships we are building with the employers are key so we can have these discussions now,” she said.

In terms of how the changes to education will shape the future of optometry, Myint highlights that there are broader factors at play.

“Education is a small part of what happens within the profession. It is an important piece – it is the cornerstone – but what we do is the starting point,” she said.

Will Holmes, immediate past chair of the OSC and a senior optometry lecturer at the University of Manchester, also believes that factors beyond education will shape the future of the profession.

He points to political questions about what roles optometrists will be assigned within the NHS and funding of professional placements relative to other healthcare professions as examples.

“If you were to ask me, ‘What does the perfect optometry programme look like?’ my answer would be to go back further and sort out some of the bigger structural issues within the profession. Education swims in all of that.”

A key focus for Holmes, who is an AOP Councillor, is championing the idea that the education of optometrists should be evidence-based.

He shared that there can be a temptation for educators to teach others based on their own preferences or experiences of learning.

“I know how easy it is to slip into intuitive ways of doing things. But this does not always fit in with the health education literature – we need to use educational approaches that are evidenced, not simply what has worked for us,” he said.

Asked why the education of optometry students should be based in evidence, Holmes highlighted that this approach helps to maintain the integrity of the university.

“There is an expectation that we should take an evidence-based approach for our students as well as our patients,” he said.

“It would be hypocritical to highlight to students that you must look at the evidence for a particular ocular intervention but not apply the same sort of thinking to our educational practice,” Holmes emphasised.

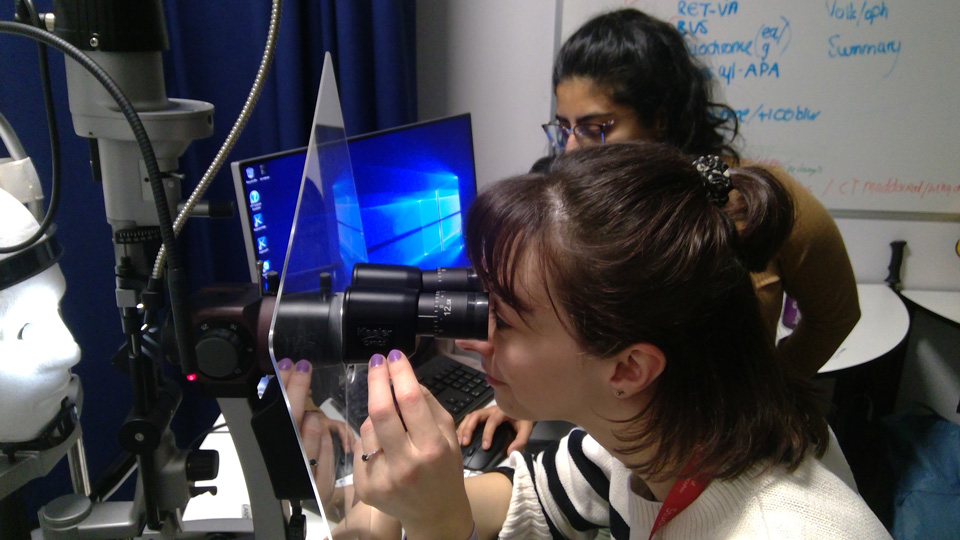

Rupal Lovell-Patel is the academic lead for vision sciences at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), which launched its new Master of Optometry course in September.

Students studying on the course are registered dispensing opticians or contact lens opticians, who continue to work in practice alongside their study.

Lovell-Patel shared that the main change to the course has been aligning the learning outcomes of each module to the new GOC outcomes.

“I think the underpinning knowledge will still remain. What does show up in the new outcomes is a focus on the behaviour of the clinician,” she said.

Lovell-Patel added that there is a greater emphasis on communication and leadership skills as well as life-long learning.

We want to make a difference in someone’s life who will then go on to make a difference in many other lives

While academics attempted to instil these attributes under the previous framework, students had less incentive to prioritise them because they were not assessed by the GOC.

“Sometimes when they are in that assessment mode, they forget that there is a human being there and the holistic approach you need to take,” Lovell-Patel said.

She hopes that graduates of the new programme will be strong communicators, who provide evidence-based, patient-centred care.

Lovell-Patel, who has worked in academia for 25 years, shared with OT that watching students develop over the course of their study is what motivates her in her job.

“We want to make a difference in someone’s life who will then go on to make a difference in many other lives,” she said.

The student view

Chris Sunderland, a student on UCLan Master of Optometry programme, began working in optics 11 years ago as an optical assistant.He is now a qualified dispensing optician and has a clear idea of the type of optometrist he would like to become.

“Where I work, many of the optometrists will have patients who only want to see them because that optometrist has done right by them,” he said.

“That is my aspiration as an optometrist. I want people to think, ‘He did a really good job. I will go back to him’,” Sunderland shared.

He has found being able to call on the expertise of practice-based educators – an element of the hybrid-learning model at UCLan – a valuable part of the programme.

“You have not just that knowledge base but a wealth of experience that goes with it. It is less of a textbook answer, but someone saying ‘This is the reality of the situation and what happens in practice’,” Sunderland said.

Sarah Owen, also a qualified dispensing optician, had some uncertainty entering the course about how the programme would unfold – and how she would manage full-time work alongside study.

“I was a little apprehensive – I knew the course was changing. I didn’t know what to expect until I was there,” she said.

“We are just about two months in, and I am starting to find my feet with my routine. When you get home and you are tired, you think ‘I would rather be on the sofa watching telly’ but then you remind yourself of why you are doing it,” she said.

She looks to her mentor – who has done independent prescribing and a medical retina qualification – for inspiration.

“No day looks the same for her. Some days she is doing routine testing. Other days she is doing foreign body removal. She is able to do so much,” Owen said.

“To be able to help patients and ease the burden on the hospitals, I think that makes sense. I want to be able to do that when I qualify,” she shared.

Fellow student and dispensing optician, Deepali Poojara, supports the emphasis on developing well-rounded clinicians in the new GOC framework.

“I have worked in practice for five years. I can see how important it is to communicate with patients,” she said.

“When a pre-reg starts in practice having done the undergraduate course, they might still be developing their communication skills,” Poojara observed.

Poojara also believes that an emphasis on understanding how optometry practices operate as businesses is important.

“At the end of the day, most optometrists do work in community practices. The optometrist has a vital role in helping that business to grow,” Poojara emphasised.

Poojara explained that her mother, who has dry eye disease and glaucoma, was part of her motivation for studying optometry.

“For me, understanding more about those conditions sparked my interest,” she said.

“When I was able to explain the condition to her, she told me ‘No one has ever explained it to me like that.’ If I can do that with my mum, then maybe I can do that with other patients,” Poojara shared.

The future of regulation

In the background to changes to the education of optometrists, the GOC has been taking a fresh look at the legislation that underpins optometry, the Opticians Act 1989.

A four-month consultation in 2022 received 353 responses on the need for change in a range of areas – including business regulation, delegation of refraction and the sale and the fitting of contact lenses.

Following the consultation, the GOC decided to call for legislative change that would ensure mandatory business regulation for optical businesses. At present, it is estimated that around only half of optical businesses are regulated in the UK.

Regarding the delegation of refraction, the optical regulator decided against pushing for legislative change that would permit dispensing opticians to refract.

“Our main concern is undetected pathologies, including subtle clues about eye health that may be missed if different professionals conduct the refraction and other components of the sight test,” the optical regulator stated.

Optometrist, Azzam Shweiki, is the chair of Kensington, Chelsea, Westminster Hammersmith and Fulham Local Optical Committee.

Shweiki explained that his LOC made a submission on the call for evidence to ensure that the GOC had an understanding of what is happening in practice.

“What optometrists see and experience in practice is essential feedback. The voice of people who are dealing with these issues on the ground is the voice that should be the loudest,” he said.

Shweiki believes that mandatory regulation of optical businesses could place a disproportionate strain on independent practices.

“We need the small independents that exist in places where the big companies would not want to establish a practice. If we make it hard to open a practice in a small village, we are denying those people that live in the village the right to eye care within their own community,” he said.

Optometrist Mark Waine contributed to the Bexley, Bromley and Greenwich Local Optical Committee submission alongside his colleague, dispensing optician Lesley Reid.

Waine and Reid work in a practice that is located within a dental surgery, where the dental nurses need to be registered and complete continuing education.

The LOC called for optical assistants to be registered with the GOC as part of its submission.

“An element of professionalism should be engrained in that career. You would have a minimum standard required to perform the job across the whole of the UK, rather than variation from place to place,” he said.

Optometrist David Knight, of Northumberland, Tyne and Wear Local Optical Committee, surveyed the group’s 150 members before submitting its response.

“We got about 60 replies which is a significant chunk of the footprint. We were very pleased with that,” he said.

Knight highlighted that despite the high response rate, he would have liked to see more young optometrists making submissions on the call for evidence.

“Who is it going to affect the most? It is going to be the newly qualified optometrists and the younger people within the profession. They are the people who probably have the quietest voice,” he said.

Knight, who has a degree in computing alongside optometry, emphasised the need for regulatory change to keep up with developments in artificial intelligence technology.

“Automation is coming. It is a rarity now but it will be commonplace in 10 years’ time,” he said.

“My personal view is that regulation is really going to struggle because the rate of change is way faster than regulatory mechanisms are adapting,” he said.

Looking ahead, Knight believes that teleoptometry will play a key role.

“That is the future, but it should be done with patient safety as a priority rather than commercial interests,” he said.

The voice of people who are dealing with these issues on the ground is the voice that should be the loudest

Professor James Wolffsohn, who compiled a submission on behalf of Aston University, shared his view that some mandatory regulation of optical businesses is particularly important now professional placements are built into university courses.

“We are making a commitment to students to provide them with the required Clinical Learning in Practice. Industry, of course, have their own aspirations of what they want the students to do during this time. That has got to be very carefully balanced,” he said.

Wolffsohn emphasised the risks of separating refraction from the eye health check.

“We are a health profession. As part of that we do identify refractive error, but the minute you divorce that from the health check you really do risk damaging the health of the nation.”

Wolffsohn would also like to see professionals who have trained in countries where optometry is advanced – such as Canada, the US, Australia and New Zealand – face fewer hurdles before they can practise in the UK.

“It would help mobility. By making it difficult for other nations, essentially we are making it difficult for our own optometrists. That exchange of ideas and practice is both good for the profession and good for patients.”

Behind the cover story

3 images

Insight from Italy

In discussing the implications of separating refraction from the eye health check, submissions from the AOP, Aston University and the Optometry Schools Council all referenced research outlining the Italian model of optometric practice.

In Italy, optometrists do not routinely conduct a comprehensive eye health assessment as part of the sight test.

Dr Riccardo Cheloni, who trained and practised as an optometrist in Italy before moving to the UK, explored this model in the article Referral in a routine Italian optometric examination: towards an evidence-based model.

As part of the research, Cheloni and his co-authors were commissioned by an optometric society to create suggested referral guidelines for Italian optometrists.

“Due to the lack of regulation in the Italian setting, there is no clear guidance for referrals,” Cheloni shared.

“The main limitation within optometry in Italy at the moment is the lack of specific regulation determining what exactly optometrists can do, which also hampers the possibility of assessing or checking the standard of practice that is delivered,” he explained.

Cheloni shared that optometrists are not legally required, trained and allowed to conduct a full ocular health assessment. Ophthalmologists are the only professionals responsible for the detection and management of ocular conditions, he added.

“There may be a significant portion of patients visiting optometry practices who are asymptomatic but still could be at risk of eye conditions that could result in preventable sight loss,” he said.

Cheloni does not believe that regulation should change to allow separation of the different elements of the sight test.

“I feel like the UK is in a very good position, in which an ocular health assessment is conducted alongside the refraction,” he said.

Refraction is a large part of what brings most people to seek eye care, Cheloni highlighted.

“If, at the same time, you can check whether their eyes are healthy, that is a bonus. You can do a great job in terms of early detection of asymptomatic eye disease and screening of common general health disorders,” he said.

Main image: Academic lead for vision sciences, Rupal Lovell-Patel, photographed at the University of Central Lancashire.

Advertisement

Comments (0)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in