- OT

- Life in practice

- Practitioner stories

- “Cultural awareness is a very important skill to have, especially in a profession such as optometry”

What I have learned

“Cultural awareness is a very important skill to have, especially in a profession such as optometry”

Senior lecturer at The University of Melbourne, Dr Kwang Cham, and students Jonah and Tiffany, share how creative responses to the topic of professionalism and cultural awareness can enhance understanding

9 min read

Jonah Krznaric

06 March 2021

Can you give us a brief introduction into your module?

Dr Kwang Cham (KC), senior lecturer in the Department of Optometry & Vision Sciences: The University of Melbourne offers a four-year postgraduate Doctor of Optometry programme. This creative-based project is embedded within a subject titled ‘Preclinical Optometry’ in the first year of the programme.In this project, each student is required to develop an original creative piece (artwork, poem, video, comic strips) that relates to professionalism and/or cultural awareness. As well as attending Zoom meetings with an allocated peer for feedback; students are required to record a three to five-minute video explaining their reason for creating the piece. Students also submit a 500-word reflection essay on the overall learning experience and submit a written copy for peer critique.

What do you feel is key to professionalism and cultural awareness?

KC: From an educational perspective, the key is setting the scene right from day one. These important attributes need to instilled into the student mindset as early as possible. The teachings of it should be integrated and scaffolded across the whole programme, and not just as a silo. The learning of these attributes is continuous and it will take time for students to develop them.As an optometrist, being culturally aware will facilitate communication and allow trust and rapport to be built more effectively with patients

How important is cultural awareness to the patient-practitioner relationship and why might this be particularly important for prospective optometrists to learn?

KC: Australia, like any other country, is a multicultural society. As an optometrist, being culturally aware will facilitate communication and allow trust and rapport to be built more effectively with patients. Showing respect for one’s culture and acknowledging the tension between clinical practice versus patients’ beliefs is important. Rather than assumed or learning on the job, or, via informal interactions, it should be taught and assessed formally. I propose that optometrists need to cultivate these attributes whilst training, and not later.Do you feel there is enough coverage of professionalism and cultural awareness in optometry education and training?

KC: The definition of professionalism is inconsistent within the literature and there are so many aspects that encompass it, such as communication. Likewise, cultural awareness, sensitivity, competency and cultural safety are different areas that students need to be competent in too.These core attributes are often overlooked due to the emphasis on optometric skills and knowledge in an already crowded curriculum. More focus is needed in optometry education and training in these areas. Areas that require further exploration include how to assess these areas and how students translate the learnings into clinical practice.

Showing respect for one’s culture and acknowledging the tension between clinical practice versus patients’ beliefs is important... I propose that optometrists need to cultivate these attributes whilst training, and not later

How do you feel your creative approach helps students to explore the topic and consolidate learnings?

KC: Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, students used to undertake an object-based learning project in groups. This involved visiting museums or galleries and selecting cultural artefacts that relate to professionalism and/or cultural awareness. This concept came from my collaboration with Professor Helen Chatterjee and Dr Thomas Kador from University College London, and Dr Heather Gaunt, who is a curator at the Percy Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne.The benefits of object-based learning on clinical education is well-established and I wanted to trial it in optometry education. I wanted students to develop creativity and divergent thinking as there is a wealth of literature on how these future work skills can enhance employability.

Students found the activity refreshing and it encouraged them to think outside the box. It has also helped them understand the topic better rather than the conventional lecture, which can be a bit dry at times.

What has been something that has stood out to you from the responses?

KC: With the constraints and restrictions due to the pandemic, I had to change the format yet retained the creative elements of the project. That’s how the creative-based project came about. From the reflection essays, it seemed the students, who are typically from a science background, were hesitant and sceptical initially. Being creative is not something they are used to, and they felt they knew what professionalism and cultural awareness meant. This project, over the course of six weeks, allowed them to slowly see the change in themselves. By the end of the project, students were impressed with the works they had created and were surprised they can be creative. They welcomed the atypical assignment and it was fun and refreshing. More importantly, through their own self-directed independent learning, they gained a deeper understanding of professionalism and cultural awareness.Could you tell us about your creative reflection on the meaning of professionalism and cultural awareness?

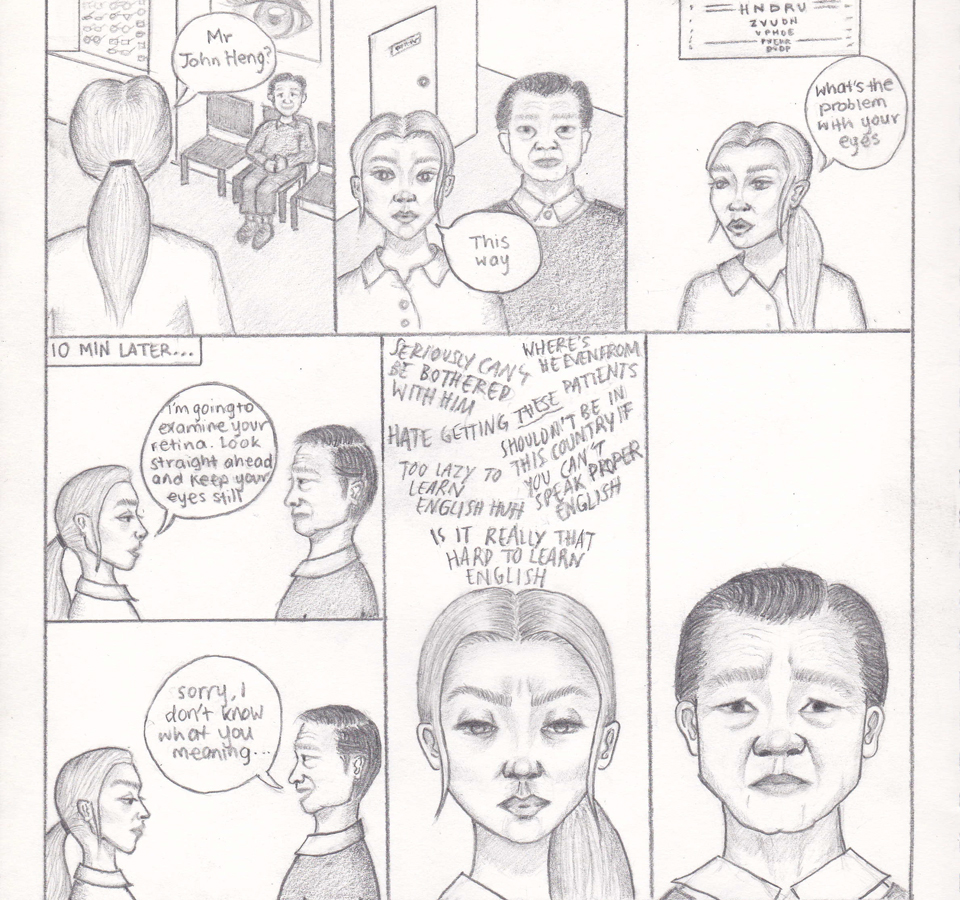

Jonah Krznaric (JK): My piece [pictured above] mainly focusses on the theme of cultural awareness. While I was reflecting on what cultural awareness means to me, I realised that every individual we come across has a unique perspective of the world that has been formed from their own experiences and culture. As optometrists, we need to first be aware of cultural differences, and be sensitive to them. Then we can provide a service where cultural safety can be achieved for everyone. For my piece, I decided to create nine different eyes using nine different artistic techniques. These were meant to represent a variety of different patients that I could potentially meet as a practising optometrist.Tiffany Lim (TL): The optometrist in my comic [pictured below] regards her patient – an elderly Asian man – with prejudice. However, on examining his fundus with her direct ophthalmoscope, something strange happens and she sees images that have been on his retina. In other words, the things that he has seen. These images were inspired by the experiences of my parents, who migrated to Australia 40 years ago having escaped the Cambodian Genocide, and real things that they have seen. From these images, the optometrist in the sketch is able to gain some understanding of the patient’s life, as well as the part that she plays in it.

Tiffany Lim

Tiffany Lim’s creative response to the topic of professionalism and cultural awareness focused on approaching patients with empathy, drawing on the experiences of her own parents

My comic is a play on the importance of seeing things through the patient’s eyes, not just in the literal sense through the direct ophthalmoscopy, but also in the figurative sense. To me, being professional and culturally aware in a healthcare setting is about empathy, in the sense of being aware of what we don’t know. It is important to be cognizant of the fact that any understanding of a patient’s life gained in a 40-minute consultation could not possibly encompass the full weight of their experiences. So, my comic was meant to emphasise the importance of consciously letting empathy and awareness lead interactions with patients of all cultures and backgrounds.

What made you choose the medium and topic that you opted for?

JK: I chose to use these different mediums to represent how, behind the eyes we treat, is a unique person who has lived a life as vivid and as complex as our own. I don’t consider myself an artist, so when creating these different eyes, I had to learn the artistic techniques. This represents to me how I will need to also learn about my future patients and their own cultures to ensure I can give them the best possible care. We need to treat all our patients as unique individuals with their own distinctive worldview, shaped by their culture and experiences. Being aware of and sensitive to this can make us better communicators and optometrists.TL: I started drawing from a young age and gladly took the opportunity of this creative assignment. I decided that expressing the emotions and experiences of the characters in a visually stimulating manner would best convey the overarching message and themes. There is a rich diversity of cultures here in Australia, and many patients come from an immigrant background. For this reason, I wanted to do something that drew quite personally from my parents’ experiences, whilst also exploring shared experiences that could perhaps resonate with people from a similar background. The comic emphasises not only the opportunity but responsibility that optometrists have as healthcare professionals in ensuring that this sector is a safe and welcome place for everyone.

How do you feel the module on professionalism and cultural awareness has helped to prepare you for a career in optometry?

JK: I think that being aware of and sensitive to the different cultures of the patients I will see in the future will help them to be comfortable and to trust us to provide the best care possible. I live in Melbourne and there are people from all over the world who also live here, so cultural awareness is a very important skill to have, especially in a profession such as optometry. It is important to make everyone feel safe and at ease. I would like to think that in the future, this learning experience will have helped me to recognise cultural diversity in my patients so that I can give them the highest standard of care, no matter who they are or where they are from.TL: Through the module I have gained an appreciation of the mental transition that must be embarked on from being a student to being a professional. I find myself reminded that solely theoretical and practical knowledge and skills aren’t sufficient for us to operate in a professional sphere which demands that we engage with people and situations that do not follow any given formula or rulebook.

When I practise in the future, I think these learnings will translate to an ability to access different approaches and modes of thinking, in order to practise patient-centred care. They are also preparing me to enter a wider healthcare landscape that goes beyond optometry. This landscape encompasses aspects such as collaboration with other areas of the community and other sectors of healthcare, but also the inequities, such as the health gap experienced by Australian First Nations’ People. It has reinforced the importance of educating myself on other cultures and their history, which I think is an ongoing process that will go beyond being a student or even an optometrist. I’ve also developed more understanding of my own identity as an Asian Australian, which informs me in how my cultural background influences my interpretation of the world, and therefore my interactions with patients.

What is a key takeaway you have gained on professionalism and cultural awareness?

JK: For cultural awareness, I think the main thing is to be respectful and considerate of the patient you are treating. Everyone deserves quality eye care, so if we can make the experience comfortable and pleasant, then I think people will be more inclined to have regular eye tests to maintain the health of their eyes.TL: I think healthcare can be a deeply personal aspect of people’s lives, so the way in which we communicate with patients and approach learning about their health and lifestyle has compounding ramifications in the greater context of their lives.

Comments (0)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in