- OT

- Life in practice

- Practitioner stories

- “Mafalda is part of my soul”

My vision

“Mafalda is part of my soul”

A girl facing sight loss counts the number of steps between her favourite tree and the moment she can see it. Author Paola Peretti tells OT why writing her first novel was a process of catharsis

Paola Peretti; Michael Crossland

05 April 2019

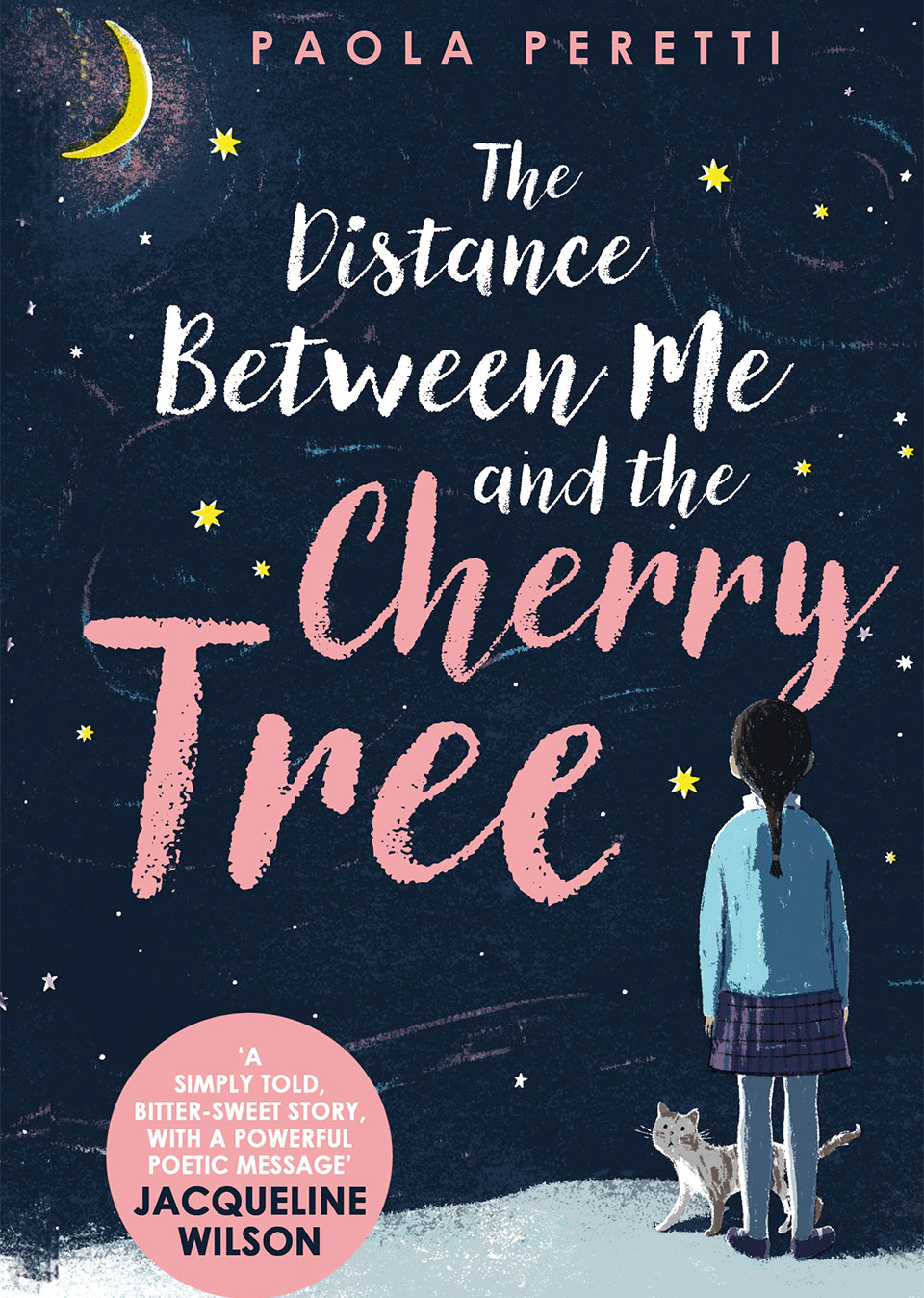

My novel, The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree, is about a nine-year-old girl who discovers that she will become completely blind in a few months’ time as she has a serious problem with her vision. She starts writing a list of what she won't be able to do any more in her darkness and what she can still do.

She also counts how many steps there are between her favourite tree, a big cherry tree in the garden of her school, and the moment she can see the tree. The decreasing number of steps represents the gradual failing of her sight, and the tree also represents, for her, a world of memories and hope.

I was inspired by many things, but above all the need to talk about my condition. Writing the book has been a process of acceptance for me. I took inspiration from my love for books and stories. The characters and the things they do in the novel are inspired by real people and their lives, for example, the foreign students that I teach.

The wonderful response to the novel was so unexpected for me. The readers completely understood my – Mafalda's – story. I hope people who read the book, even those who don’t have issues with their vision, can recognise that we all have to face problems in our life.

Children's books are often clear and simple in the way they are written and in their message but also intense and full of imagination

Writing relief

Writing was a way of exorcising fears for me; knowing that readers will maybe find a way to face their fears reading my book makes me happy. I also enjoy putting references to other books and characters into the story – as a reader, I've always had great pleasure finding references to other books when I was reading.

I think that reading an inclusive book for children can be enjoyable and also useful for adults, whether they read it with their children or alone. Children's books are often clear and simple in the way they are written and in their message but also intense and full of imagination.

I like to say that I have an alternative way of seeing things; however, the cold truth is that I'm always the most short-sighted person everywhere I go. Thankfully my vision is currently stable, but I don't know how long this situation will last, so I work as much as I can. I don't want to waste time and my opportunity to write. Wearing glasses and using programs of magnification for working on screens help me. I can't overstrain my eyes.

I first noticed my vision loss at school, when I was 13; I couldn’t see the blackboard very well and suddenly I become the most short-sighted in the class. Because Stargardt macular dystrophy is rare, I wasn’t diagnosed until a few years after I first noticed my vision getting bad. I can't remember the precise date, but I was a young adult.

Now that I have written the book, I don't think so much about my vision loss. Writing was a sort of forced self-analysis. It has been a liberation. For years I was scared and worried and I didn't want people to know about my condition. I didn't ask for help. Now I'm more relaxed about my problems. Losing sight is not the worst thing that could happen to someone.

The book is based on my life, but I'm not Mafalda. I've never been a scared girl, and now my vision is stable. But I think that Mafalda's story, in some ways, is everyone's story, we all need to face fears and problems at some point in our life; sometimes we have to accept change to move forward and make difficult decisions to be happy again. But either way, Mafalda is a part of my soul.

The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree, authored by Paola Peretti and translated by Denise Muir, is published by Hot Key Books.

- As told to Selina Powell.

The optometrist’s view

Moorfields Eye Hospital senior optometrist in low vision, Michael Crossland, shares his thoughts on The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree

How far away can you see a cherry tree from? This unusual measure of visual acuity explains the title of The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree, a new young adult book by Italian author Paola Peretti.

It tells the story of Mafalda, a nine-year old girl with Stargardt disease. Mafalda describes her life and innermost thoughts as her “cherry tree distance” falls from 70 metres to zero. Alongside her failing sight she describes more common “tween” experiences: changing friendships, her first boyfriend, moving house, and her grandmother’s death.

The author has Stargardt disease, and the book provides a realistic view of life with low vision. Mafalda will use her magnifier only in the school toilet, and describes the problem of low contrast sensitivity very well.

“The floors in my school are light blue, the walls are grey, and the doors light blue and grey. It’s like running though nothingness. I come to stop with a bang, my whole body slamming into the door of the caretaker’s room,” Peretti writes.

The caretaker is a compelling character: a grumpy middle-aged woman, she has no patience with Mafalda feeling sorry for herself. As the story progresses, we see how helpful her unusual counselling is to Mafalda, and we learn about the caretaker’s own hidden health problems.

Many professionals could learn from some poor communication skills described in the book. As her ophthalmologist breaks bad news her voice drops until: “I’m not sure I understand what she’s saying, although it occurs to me that maybe I could have tried harder in the tests…I’m about to say this to the doctor, but she keeps speaking in tones so hushed I have to point my ear to her mouth to hear.”

Other characters are more sympathetic to people with low vision. In a moving scene, Filippo, Mafalda’s boyfriend, uses a thick black marker pen to write a love letter so Mafalda can read it. Sadly, many teachers don’t grasp the importance of high contrast text, let alone school children!

If Filippo’s actions are unusual for someone so young, some of Mafalda’s writing is even more precocio us. “It’s not that love makes you better; it just makes you less afraid of bumping into things” is a lovely phrase but would a nine-year old really have said this? How many under-10s would describe their parents’ reaction to bad news as “Mum and Dad crumple in their seats like burst balloons”?

At the same time she remains childlike – her naivety about sex and reproduction is scarcely believable in the internet era. And would school be happy with her spending her breaktimes in the caretaker’s office?

Although losing sight so quickly and so completely may have been the author’s experience, it is unusual. Typically, Stargardt disease presents in someone’s teens, progresses over many years and leaves peripheral vision intact.

Even people with the most severe Group 3 form of Stargardt disease, who are most likely to develop profound vision loss, tend to lose their sight over years rather than weeks. This means the book may be unrealistically pessimistic for a child newly diagnosed with Stargardt disease, and readers with affected relatives should understand how unusual Mafalda’s case is. Despite this, The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree gives a fascinating insight into the world of childhood visual impairment.

Comments (0)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in