- OT

- Life in practice

- Career development

- Training the IP workforce

IP: an upskilling workforce

Training the IP workforce

As the number of IP optometrists grows, OT reviews the obstacles to qualification, in the first of a new series of reports

07 November 2022

The qualification process for independent prescribing (IP) has always had its challenges, as any qualification might, but some have only become harder following the pandemic. Meanwhile, we are seeing more discussion of extended services, a new NHS structure, and the General Optical Council’s (GOC) new requirements which will bring changes that could reshape the training of IP optometrists.

In the first of a new series that will explore the scope of IP optometry – present and future – OT sought to look into the training and qualification of the increasing numbers of IP optometrists.

The numbers

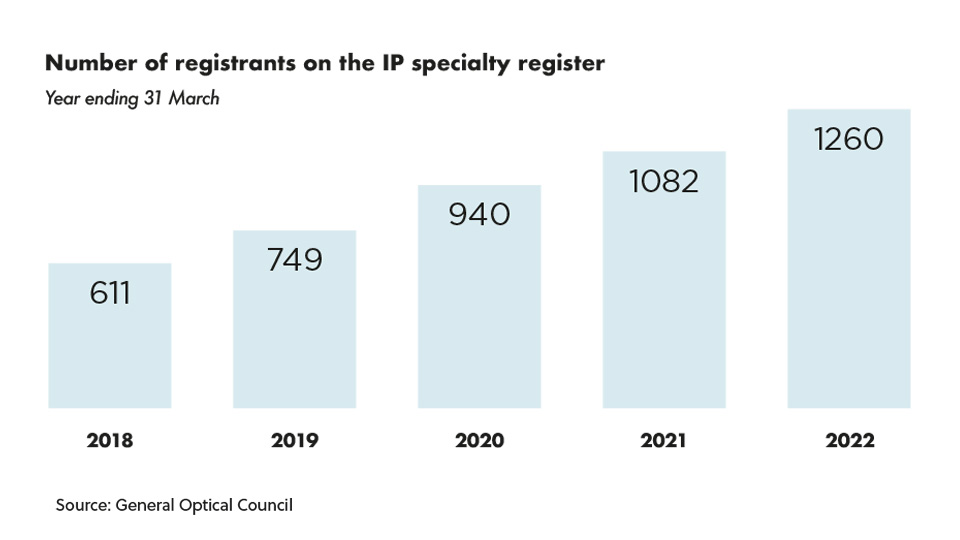

The number of registrants on the GOC’s independent prescribing specialty register has grown by 37% in the past five years, from 611 in March 2018 to 1344 as of 28 July 2022.As the numbers continue to rise, interest in undertaking the qualification appears to be growing too. The GOC’s Registrant Workforce and Perceptions Survey 2022 found that 40% of respondents planned to gain additional qualifications or skills when asked about their career plans over the next 12 to 24 months.

Common reasons given for this centred around delivering better care and more services, helping more patients, and expanding their scope of practice, as well as for career progression.

Reflecting on this, Samara Morgan, head of education at the GOC, told OT: “It’s positive to see that so many optometrists are considering upskilling,” suggesting that this could be as professionals seek to gain a competitive edge in advanced multi-disciplinary environments, or to help ease the pressure on secondary care with a wider range of optical health services delivered in local settings.

The College of Optometrists has also reported growing numbers of optometrists taking up IP – evident in the number of candidates taking its Therapeutic Common Final Assessment (TCFA) in IP, the final stage before receiving the qualification.

In 2021, 200 candidates sat the TCFA in IP, with 183 passing. This was a 32% increase in candidates compared to 2020, in which 152 people took the exam and 122 passed.

So far in 2022, with two out of the three exam periods for the TCFA completed at the time of writing, 158 candidates have sat the exam and 140 passed.

Speaking to OT about the data, Lizzy Ostler, director of education for the College of Optometrists, suggested: “The increase may be due to the greater role the profession is fulfilling, particularly within new integrated eye care services and enhanced or supplementary care schemes.”

Optometry departments at universities across the UK all described high levels of interest in their IP courses to OT.

Ulster University has seen interest rising, especially from experienced clinicians wishing to expand their scope of practice, explained Dr Julie McClelland, senior lecturer in optometry and course director for the Theory of Independent Prescribing for Optometrists, and Patrick Richardson, lecturer in optometry, optometry clinic manager and an independent prescribing optometrist.

The lecturers recognised the role of the pandemic in this, sharing: “Many practitioners made adaptations to their usual provision and worked closely with local GPs, pharmacists and ophthalmologists to improve access to eye care and, as a consequence, they can see how gaining the IP qualification would help to facilitate this and ensure an ongoing enhanced level of eye care.”

The pandemic impact

With demand high in the pandemic, a number of universities received permission from the GOC to create special cohorts or create additional spaces for a period off time.

In June 2020, with many practitioners unable to complete full-time work, Glasgow Caledonian University used the opportunity to provide additional theoretical IP training. This was enabled through extra funding provided by NHS Education for Scotland (NES) and the Scottish Government.

“During 2020–21, approximately 220 students completed our course, compared to approximately 100 in previous years,” Dr Mhairi Day, senior lecturer of the Department of Vision Sciences, said.

The University of Hertfordshire ran its first cohort of five students in January 2020, and had to quickly adapt to online teaching and assessments as the pandemic broke. But because of the lockdown, Colin Davidson, principal lecturer in optometry and programme lead for optometry independent prescribing and higher qualifications, said: “We had a huge increase in demand of optometrists wanting to study IP.”

The university gained special permission from the GOC to run a second cohort of 20 students, which began in September 2020.

Ulster University also gained permission from the GOC to deliver its virtual IP theory programme to a cohort of 120 places, arranged in collaboration with Hakim Group and made up of optometrists within the group and as well as other independent practices.

A question of funding

The approach to funding appears to differ significantly across the country: a mixture of self-funding, employer support, and regional funding models.Colin Davidson, principal lecturer in optometry and programme lead for optometry independent prescribing and higher qualifications, explained that on the University of Hertfordshire’s IP course approximately half of the students are funded through their employer, hospital trusts or Health Education England, while the remaining half are self-funded.

“We’ve got nine students who are Health Education England sponsored to complete the course, and some hospital trusts funding,” he said, noting that this is due to “a lot of work” by the university and Local Optical Committees to increase interest in the qualification.

200 candidates

took the Therapeutic Common Final Assessment in IP in 2021

The College also recognised that funding and placement availability “continue to represent potential barriers to the future development of the profession.”

Engaging in the GOC’s Sector Strategic Implementation Steering Group, which facilitates discussions with the sector to support workforce planning, the College said it would continue to campaign for improved funding.

In Scotland, funded places on the IP course are available through NES, with both employed and locum optometrists able to apply annually.

IP optometrist Kevin Wallace, an AOP Councillor and clinical adviser, shared that he was part of a cohort in the first year this was offered by NES, telling OT: “It’s a big advantage in that you didn’t have to think about paying for the course.”

“Optometrists in Scotland are the first port of call for all eye problems within the community,” explained Julie Mosgrove, chair of Optometry Scotland. Scotland currently has around 400 IP optometrists – making up about 30% of the profession in the nation.

“This care is managed by all optometrists as part of the GOS package. Optometrists with IP have NHS prescribing pads and all NHS prescriptions are free of charge to the patient,” she explained, while acute ocular conditions are usually funded via a supplementary eye examination fee.

A 50% higher grant is available to IP optometrists for their annual CPD, Mosgrove said, and explained: “The Scottish Government has been working with the profession to develop enhanced GOS for IP optometrists but this programme is currently on hold whilst awaiting confirmation of funding.”

Optometrists in Scotland are the first port of call for all eye problems within the community

For Amit Sharma, an optometrist and director at a number of independent practices with Hakim Group, Pinder & Moore Opticians in Kingswinford, in the West Midlands and Davis Optometrists groups in the East Midlands, the IP qualification was something he had always wanted to do but had not been motivated to make the jump before, telling OT: “I think, clinically, it is the right progression to be able to serve my patients and the community better.”

When the pandemic highlighted opportunities to be able to further support local communities, Sharma approached Hakim Group to discuss his interest in undertaking the qualification, and they sought to establish a special cohort through Ulster University.

Sharma suggested that being presented with the opportunity from Hakim Group and Ulster University made it easier for other optometrists to come on board. Describing it as ‘win-win,’ he added: “Firstly because there was financial support, and secondly because it presented an opportunity they wanted but hadn’t had the kick to do it.”

Specsavers has enshrined support for higher qualifications as part of its career pathways and has invested “hundreds of thousands of pounds” into helping fund optometrists’ courses, explained Paul Morris, director of professional advancement for the multiple.

“I think it’s wonderful that we’ve got the opportunity to do it. We have so many institutions that are able to make it accessible to people and I don’t think the costs are huge,” he added.

Describing the support provided to optometrists within the business who want to complete the qualification, Morris said: “The people who want to go and do IP and other qualifications are so numerous, so keen, and it has a real practical use in most areas – we’ve been really happy to help fund some of that.”

In the future, he expects that independent prescribers will become “more the norm… I think you’re already seeing that in Scotland and I think you’re about to see it more in Wales as well.”

An appetite to upskill

Sharing the decisions behind launching the bursary, optometrist Mandy Davidson, medical and professional affairs manager for Scope Eyecare, told OT: “The pandemic really highlighted the important role that optometrists can play in enhanced services for patients. Scope is proud of the fact that optometrists really stepped up to the game, and saw and co-managed patients in really difficult situations. I think that made a lot of people think about IP, and consider: ‘why not?’”

But the company recognised that barriers exist for some optometrists. Davidson explained: “Some people have employers who will help but others find they can’t meet that challenge. One of the reasons for the bursary was to remove one of those obstacles.”

Over 70 applications were received for the bursary, with three optometrists selected for the reward of £1500 towards IP course fees.

The applications came from a wide range of backgrounds: from newly-qualified, to hospital optometrists, independent practice to multiples. Davidson said: “The appetite to upskill is across the board and that is really encouraging.”

“We’ve been staggered by the interest. If 50% of the people who applied decide to go on anyway then it’s a win for the profession, a win for patients, and a win for the cash-strapped NHS as well,” she continued.

Placement availability

A common concern highlighted by optometrists around the IP training and qualification process was a lack of clinical placement availability, an issue that has been consolidated by the pandemic.Angela Whitaker, IP programme lead at Cardiff University, shared both funding and clinical placements can be a concern for those thinking of studying IP.

Whitaker said that placement availability had already been a challenge, but following the pandemic, “it became even more challenging and many found it impossible. The situation has improved slightly but remains very difficult.”

Sharma explained that since Hakim Group’s cohort of optometrists completed the IP course in February 2021, the challenge has been to secure clinical placements.

“Some have been lucky, being in localities where the hospital eye service is very pro-optometry. But some have been quite restricted, limiting the numbers of people in a consulting room,” he said.

During the pandemic, changes were made to support IP training, such as allowing part of the clinical placement to be virtual.

While this was welcomed, Sharma reflected: “We thought that would open up a lot more opportunities, but it’s not changed the landscape too much from our perspective.”

The College’s Ostler acknowledged that, for many candidates, it is a challenge to find a placement with the capacity to offer experience. Responding to this, the College has agreed with the GOC to approve an extension to the timespan between the academic course and starting a placement, subject to the candidate undertaking and documenting suitable CPD. Ostler noted that candidates should contact the College if they think they may need an extension.

She added: “We will be seeking approval by the GOC to retain all these enhancements for as long as necessary to support optometrists training for the IP specialism.”

A case of connections

Optometrist Dr Keyur Patel, clinical director at Tompkins Knight & Son Optometrist, an independent practice within the Hakim Group, completed his IP qualification after a period working in the US, which he said, “really opened my eyes to therapeutic optometry.”He explained that: “I was lucky to be working in a glaucoma clinic anyway, so I was under a consultant and got some of my sessions there. I know some private ophthalmologists who were kind enough to get me into local hospital services so I could get more of my sessions there.”

But reflecting on his experience, he added: “I’ve used the word ‘lucky’ and I think at the moment it still involves that. There is a lot of who-you-know involved in how fortunate you can be to get a place.”

Fatima Nawaz, AOP Councillor for independent prescribing optometrists and ophthalmic director in an independent practice, also highlighted some of the challenges around placement access.

Nawaz was working in a multiple when she began her IP course and secured a placement in a private hospital. She said of the experience: “I was really blessed to have an amazing supervisor and consultants that didn’t mind me sitting in their clinics.”

“I’ve heard it’s really hard to get hospital placements,” she acknowledged and was grateful the private hospital gave her a supervisor as part of the placement. “I don’t think I would have had the contacts at that point, if I had to do that on my own, I would have struggled to find an ophthalmologist to supervise me.”

However, she also felt that changes could be made to the system of supporting optometrists through the IP qualification and placement, suggesting: “There needs to be better connections with ophthalmologists, maybe from the College’s side, and some incentive for supervisors,” she added.

Connection with ophthalmology seems key to furthering the ability of IP optometrists to secure placements.

Expressing his concern around placement availability issues, Morris told OT: “I think the profession as a whole needs to make more effort with ophthalmology and NHS stakeholders to make that work.”

“I would ask the College to look a little bit harder at what it could do to help, and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists to see what more it can do to promote that,” he said.

Optometrists acknowledged the pressures faced by hospital departments. Morris commented: “We’re not quite in a post-COVID-19 world yet, we’re post restrictions, and it is difficult to have too many people in too small a place… But these are the things we have to face into. We have to show people the opportunity that it is going to make things easier for them in the future.”

“I would urge everyone in our profession to develop better links with their local ophthalmology network to make sure they understand the great work we do, and how to support them better by engaging in a dialogue around feedback and all the good things that make for a healthy symbiotic relationship,” he said.

A clinic approach

In many parts of Scotland, optometrists have access to NHS-funded Teach and Treat clinics, explained Mosgrove. Overnight accommodation and travel is paid for those needing to travel a long distance for the training.“The clinics are overseen by a consultant ophthalmologist within a hospital setting, giving optometrists experience of managing and treating a variety of ocular conditions,” she said.

“Naturally pressure for placements has grown, with fewer IP placements being available during the pandemic,” Mosgrove said. Remote clinics were established in some health boards to help with the backlog and though face-to-face clinics have resumed, remote learning is still provided to those in remote and rural settings.

Scotland

has around 400 IP optometrists, about 30% of the profession in the nation

Asked if this is a model that could offer lessons for other parts of the UK, he commented: “I think it’s a really helpful model of having a dedicated training clinic. If you want optometrists to get the experience and see more of the pathology that has traditionally been seen in the hospital, that is the way to do it.”

Jill Campbell, chair of Optometry Northern Ireland, explained that services are regionalised in Northern Ireland with an IP placement scheme coordinated by the Belfast Trust.

The scheme was paused for a time during COVID-19, so there is likely to be a bottleneck, Campbell acknowledged.

“We’re very fortunate that the placements are free to the optometrist. They get a really good range of experience; they can observe glaucoma clinics, eye casualty, corneal clinics and general ophthalmology so they get a good variety,” she explained, adding that aside from the experience itself, a key benefit of the scheme is that optometrists have the opportunity to build connections with ophthalmology.

There is no specific pathway for utilising the skills of IP optometrists yet, though a pilot is in development. Campbell explained: “The profession are aware that is being discussed and Optometry Northern Ireland are leading the discussions alongside a group of IP optometrists.”

Changing requirements

Earlier this year, the GOC published updated education and training requirements for approved qualifications in additional supply, supplementary prescribing and independent prescribing categories.As part of the requirements, trainees will be required to have identified a designated prescribing practitioner (DPP) before or shortly after admission, who will supervise their approximately 90 hours of practice. The DPP can now be an appropriately trained and qualified registered healthcare professional with independent prescribing rights, rather than an ophthalmologist.

While positive changes, Dr Peter Hampson, clinical and professional director for the AOP, pointed out that these may not be a straightforward solution to the challenges at hand, due to the requirements that the DPP must meet to act as a supervisor.

Speaking to OT previously, the GOC had outlined that the DPP “must be an active prescriber competent in the clinical area(s) they will be supervising the trainee in, have the relevant core competencies and be trained and supported to carry out their role effectively.”

Hampson commented: “To fulfil the role of DPP, the practitioner would need to be able to fulfil the full range of patient types and be experienced in managing them themselves.”

“While there are some practices and practitioners with the correct case mix, unfortunately I don’t think there are that many,” Hampson noted. “While this is a positive step, it may not be the solution that some were hoping for.”

Under the new requirements, trainees will also no longer be required to have been practising for two years before taking the qualification. Discussions around the future of IP also consider whether the theory could be integrated into new optometry courses. Reflecting on the benefits of this approach, optometrists pointed to training systems in similar primary care settings.

With more optometrists taking on higher qualifications in Wales, Chris Evans, optometrist director at Gwynns Opticians, said: “I don’t think IP is going to go back into the box. More people are going to do IP. Look at pharmacy. I think we’re more likely to see that model and people expanding their scope of practice.”

However, Evans emphasised that if theory is integrated into degrees, equal opportunities must still exist for qualified optometrists who wish to gain the qualification.

Patel pointed to approaches in the US, where students have three years of didactic training and slowly build up clinical experience, with a fourth year made up of four clinical rotations in different settings. Of this, he said leaving university, graduates would have “the ability and foundations” to use IP.

However, he expressed concerns over the single point of qualification and what the oversight for this process might look like, suggesting a national board of examinations would set a minimum standard that optometrists must pass.

Others pointed out that the experience gained between graduation and returning to university for the IP qualification has its benefits.

Ulster University’s McClelland and Richardson told OT that, having delivered the IP qualification at a post-graduate level for six years, “we can see the value in optometrists having post-registration experience.”

The lecturers added, however: “The decision to incorporate IP into the undergraduate curriculum is also dependent on factors relating to funding, workforce issues and local commissioning, which vary across the UK. We look forward to working with commissioners to plan the training needs of the future members of the profession.”

The future workforce

Looking at the future for this qualification, the general consensus seemed to be that IP is the natural next step in the progression of the optometry profession.Wallace shared: “I’ve always seen it as the optometrist becomes the GP for eyes so that anybody with an eye problem knows that is where to go. Then we can deal with 90% of the conditions that come in with only a small number having to go on to hospital for specialist treatment.”

“It feels like it would be a gain for society. An efficient service, seeing patients closer to home, at a reasonable cost to the taxpayer,” he said, adding that an expanded workforce would provide the capacity need for this. “If there is funding, and everybody is doing their bit in practice, it dilutes it and keeps the volume at a level we can all manage.”

Nawaz suggested it seems like “everyone is getting set up for the future.”

However, she highlighted the scope of practice that optometrists already have and emphasised that more could be done with existing schemes, such as Minor Eye Conditions Services.

“I do think it could be a lot better than it is at the moment. I just don’t feel like we’re having the right conversations,” she said. “I feel like until we get ophthalmology on side, the changes aren’t going to happen. Whether that is them understanding what we do, or the funding, but until they give us the work then I don’t think that everyone needs IP.”

It feels like it would be a gain for society. An efficient service, seeing patients closer to home, at a reasonable cost to the taxpayer

Morris said he expects we will see a wider network of IP optometrists who would be able to see patients ordinarily seen in the hospital service.

However, he highlighted the important role that optometrists already play: “Do I think that IP is requisite for everyone? Probably not. But I do believe everyone should have the opportunity to do it in the fullness of time, depending on their requirements,” he said, continuing: “I believe IP has to be the direction of travel for a sizable cohort of colleagues over time.”

Optometrists recognised the opportunity that IP in optometry can provide; whether to the optometrist in terms of knowledge and career progression, for patients and communities who can be managed closer to home, or to support potential service developments in the future.

Campbell reflected: “The more registrants that we can get to undertake higher qualifications, the more services we can provide in primary care, the better experiences for our patients who want their care delivered in their local community with someone that they trust.”

Optometry Today will continue to explore this topic in future issues, including a focus on commissioning services that utilise the skills of IP optometrists, and the considerations that come with a new workforce of IP optometrists. To share your views on the topic, get in touch with OT at: [email protected]

Parting words on IP

Patel: If anyone is going to invest in any further qualifications, they should do IP. IP will change your life and it will change your patients’ lives. It is the qualification optometrists should be leaving university with.

Evans: The IP training has opened my eyes: what I’ve learned from it, and what I’m able to do, even down to the way I look at an eye now. I think it’s probably the best thing you can do as an optometrist in the High Street.

Sharma: I think it’s really important that we continue to develop as a profession. We’ve got to be able to offer more than just the testing of sight. Utilising the education and training we’ve done and developing ourselves further so that we can offer any forms of enhanced services.

Wallace: With an ageing population a lot of conditions will become more common and the hospitals will get busier. It makes sense that we can deal with more of these things in the community and that will require more people with the skills to look after them.

Advertisement

Comments (1)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in

Anonymous10 November 2022

I, like many others I know, have no intention of becoming IP. I have no interest in being a doctor or I would have studied medicine.

Report Like 290