- OT

- CPD and education

- Understanding the test types

Understanding the test types

Dr Lindsay Rountree introduces the most frequently used visual field tests in routine practice

03 March 2020

It is easy to get into the habit of using one type of visual field test, but each type of programme is designed for a different purpose. The optometrist will consider the pros and cons of each test when deciding on the most suitable one to use for a particular patient. It is a good idea to try the different options on the field screener(s) in practice, which can help when explaining the test to the patient. Here, we will outline the commonly used types of test.

Threshold

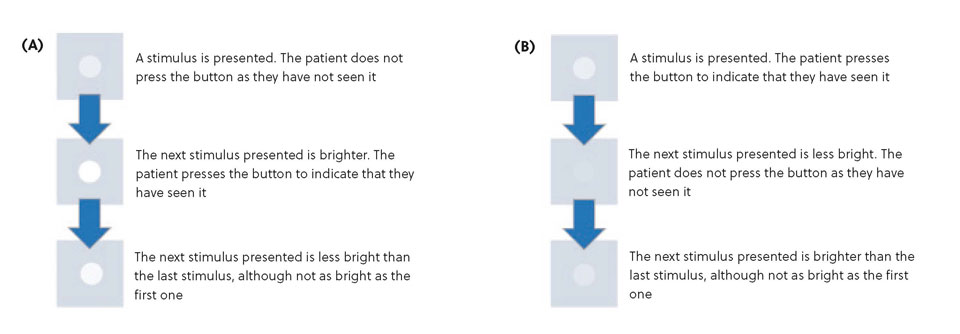

This is when a sensitivity measurement is determined individually for each location tested. This is typically based on a ‘staircase’ strategy, whereby the first stimulus (spot) presented at a location is based on the ‘normal’ values for a person of that age or based on the sensitivity of neighbouring locations. The next stimulus presented at the same location will be more (Figure 1A) or less (Figure 1B) bright depending on the patient’s response to the previous stimulus. These tests generally give a detailed overview of the patient’s vision but can be time-consuming. Some threshold tests have options to speed up the test time, while still establishing the sensitivity at each individual location, for example, the SITA Standard or SITA Fast programmes incorporated into the Humphrey Field Analyzers.

If a patient is known to have severe problems with their peripheral vision, a visual field test may still be useful in investigating their central vision

Suprathreshold

This is when stimuli are presented at a slightly brighter level than the expected sensitivity. This expected sensitivity may be determined by testing a small number of central locations at the beginning of the test in a similar manner to the ‘staircase’ strategy. Alternatively, it may be based on the ‘normal’ values for a patient of that age.

The suprathreshold stimulus used is expected to be within the visible range for that patient. If the patient indicates that they have seen the stimulus, it is assumed that no significant defect is present, and no further testing takes place at that location. If the patient does not see the stimulus, a brighter one will be presented at the same location. The report will show which stimuli were missed but does not determine an exact sensitivity at any location.

Suprathreshold tests are generally used as a pass/fail screening tool. If the patient ‘fails’ the test, it is recommended that the patient is retested using a threshold strategy. Most tests are designed for monocular viewing to identify conditions that may affect the eyes asymmetrically. However, the Esterman test is designed to be viewed binocularly and is primarily used to establish whether a patient still meets driving standards.

Figure 1

Which test to choose?

The ideal test for a particular patient largely depends on the reason for wanting them to complete a visual field test. Typically, a visual field test is used in the investigation of glaucoma, but even then, there is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that will suit everyone:

- If the patient is attending for a routine eye examination, and there are no other indications that glaucoma may be present, a suprathreshold test may be selected as the first option, followed up with a threshold test if any problems are found, to gain more information

- If there are suspicious signs that may indicate glaucoma, the optometrist may opt for a threshold test to gain that extra information straight away

- If the patient has previously been diagnosed with glaucoma, a threshold test is usually required, and it is recommended that any follow up tests are carried out with the same instrument and testing strategy. This is partially because different instruments have different ‘brightness’ ranges, that is to say, the decibel values are not equivalent - 30dB with one instrument may not be the same brightness as 30dB with another instrument. In addition, different normal values are incorporated into specific machines, and different algorithms can also influence the outcome of the test. As such, it is not possible to easily compare the results of one visual field test to another.

The ideal test for a particular patient largely depends on the reason for wanting them to complete a visual field test...There is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that will suit everyone

If signs or symptoms are present which could indicate problems further along the visual pathway, tests designed specifically to investigate glaucoma may not be suitable. A defect in the brain may not be identified by a test that only extends to 30°, so it might be better to select a test which presents stimuli further out in the periphery.

If a patient is known to have severe problems with their peripheral vision, a visual field test may still be useful in investigating their central vision. Depending on the extent of their field loss, a test that extends to 30° may not be appropriate, as the patient may not be able to see the majority of the stimuli presented; this can extend the length of time the test takes to complete, and can make patients anxious if they have to wait for long periods of time between seeing stimuli. A test that extends to, say 10°, will give a detailed investigation of the patient’s useful vision, which may be more beneficial.

Other articles in this series

- In the field Optical assistant, Lisa Skelton, discusses carrying out visual field tests

- A perfect match How artificial intelligence is being applied to visual fields

- The visual pathway Dr Samantha Strong shares a journey through the visual pathway

- The patient and the visual field test Dr Lindsay Rountree discusses making the patient’s experience of visual field testing a positive one

- What the future holds Dr Laura Edwards and Dr Lindsay Rountree discuss their take on research into visual field

- Visual fields: the jargon OT explores the terms commonly used on a visual field plot

Advertisement

Comments (1)

You must be logged in to join the discussion. Log in

Don Williams03 March 2020

I do a lot of kinetic perimetry and I still think that there is a place for the 'old Goldmann visual field'. I get really good results with the GVF.

Report Like 684